GREENVILLE, S.C. (AP) — In a different time, it was an attractive little two-bedroom home, constructed in the early 1940s out of red brick and owned by one of the greatest players ever to grace the diamond, a towering yet tragic figure who lived the last half of his life and went to his grave as a pariah, shunned and scorned by the national pastime.

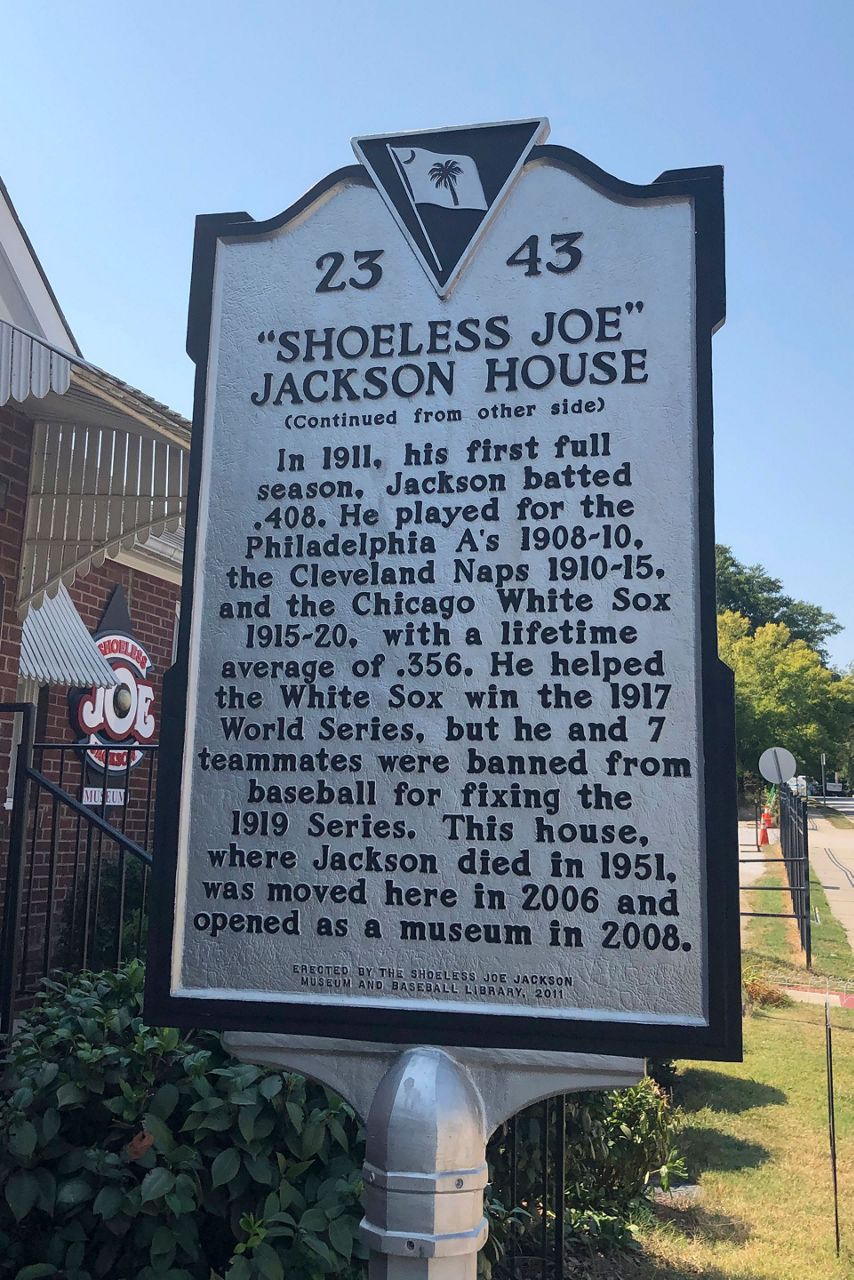

Now it's a museum, right across the street from Greenville's retro minor league ballpark, dedicated to preserving the memory of the man who once lived within its walls.

Shoeless Joe Jackson.

"It is one of the greatest stories," says Michael Wallach, who leads the museum's board of directors. "So many of the baseball players in the Hall of Fame, their story is their career. Joe has three parts to his story: before, during and after. All three are romantic stories."

Growing up in a Southern mill town without a day of formal schooling.

A brilliant baseball career that was snuffed out in its prime.

The life he built after being kicked to the curb by the game he loved.

Even now, on the 100th anniversary of the Chicago White Sox finishing off their infamous throwing of the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds, stamping themselves for eternity as the Black Sox, Shoeless Joe stirs up harsh feelings and fierce debate about his place — or, more accurately, non-place — within the game.

Well, this is not a plea to exonerate a man who surely made some awful mistakes.

It is a call for compassion.

Jackson's century-long banishment is long enough.

Say it's so, Major League Baseball.

Put Shoeless Joe back in the game.

___

"God knows I gave my best in baseball at all times and no man on earth can truthfully judge me otherwise."

The highfalutin words, plastered on the side of the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum, might ring hollow to those who know him largely as the most prominent of eight White Sox players who allegedly conspired with gamblers to lose a World Series.

To this day, it remains baseball's greatest stain (sorry, Steroids Era).

On Oct. 9, 1919, Chicago completed the shameful deed with a 10-5 loss in Game 8 of the best-of-nine series, handing the championship to the Reds by a margin of five games to three.

White Sox starter Lefty Williams did his part in the decisive contest by giving up four straight hits after getting his lone out, putting his team in a four-run hole before it ever came to bat. With three losses in three starts, there is little doubt about his guilt. Ditto for first baseman Chick Gandil, shortstop Swede Risberg, pitcher Eddie Cicotte, center fielder Happy Felsch and utility infielder Fred McMullin. Third baseman Buck Weaver is a more complicated figure, apparently aware of the plot but not taking part.

Then there's Shoeless Joe.

While there are conflicting accounts as to what he acknowledged, Wallach concedes that Jackson accepted $5,000 from the gamblers and was fully aware of the scheme. But his performance on the field largely seems to back up the claim Shoeless Joe made for the rest of his life.

He played to win in 1919.

Jackson batted .375 with a Series-record 12 hits — a mark that stood for 45 years. He hit Chicago's only homer (this was at the end of the dead-ball era) and led his team with both five runs and six RBIs. He struck out just two times in 32 at-bats, handled 30 chances in the outfield without an error and was posthumously figured in the sabermetrics world to have tacked on 0.58 wins (known as win probability added, or WPA) to his team's total. That was the second-highest total for any player in the Series, surpassed only by teammate Dickey Kerr, who wasn't in on the fix and won both his starts with a 1.42 ERA.

"If Joe Jackson was throwing the World Series," Wallach scoffs, "that was not the way to go about it."

___

Even though all of the Black Sox were acquitted at a celebrated 1921 trial, baseball moved quickly to remove a scourge that threatened its very existence.

Gambling and fix allegations were as much a part of the game as balls and strikes, so the owners appointed former federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis to clean things up. Despite the courtroom verdict, the powerful new commissioner banned all eight players for life — a harsh edict that stands to this day.

Wallach actually has no problem with Landis' decision.

"Baseball was going to fall apart if Kenesaw Mountain Landis did not come in and say, 'There will be no cheating in baseball,'" Wallach says. "Now, would I have forgiven Joe before his life was over? I think so. Why? Because that's who America is. America does not hold a grudge if someone shows remorse and asks for forgiveness."

Jackson, who couldn't read or write, relied on his wife, Katie, to fire off letters pleading for his reinstatement. All were ignored. He actually received two votes in balloting for the initial class to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936 and was still getting a modicum of support a decade later but has been formally barred from any consideration under rules passed in the wake of Pete Rose's banishment from the game.

Jackson died in 1951, three weeks before Christmas at the age of 63 (or perhaps 64), in what was a small bedroom but now houses various artifacts related to his life. A wooden seat from Comiskey Park. A set of dishes. A battered old glove. Even a picture of the white-haired Landis, staring back sternly from the great beyond.

Wallach disputes the notion that Shoeless Joe died a broken man. He hated being known as a cheater but played in the minor leagues into his 40s, sometimes under an assumed name, or with outlaw teams that weren't governed by organized baseball. He owned a liquor store and a dry cleaning business, while his wife invested in real estate and probably would've been called a house flipper in today's world. The couple never had any children but seemed to live a comfortable, generally happy life.

They are now buried side by side in Woodlawn Memorial Park, not far from their home-turned-museum. There are no signs pointing out their gravesite in the sprawling cemetery, but everyone seems to know where is. Avid fans, who perhaps view Jackson through the sympathetic prism of movies such as "Eight Men Out" and "Field of Dreams," still leave baseballs and cleats and bats around the simple bronze gravestone. When someone arrives in search of Shoeless Joe's resting place, all they need do is ask a worker on the grounds.

"Joe Jackson's grave? You mean Shoeless Joe?" one drawled when this intrepid reporter came in search of it not too long ago. "It's right over there."

___

Time supposedly heals all wounds.

Yet, even if Jackson's ban is lifted, it seems highly unlikely he would ever get into the Hall of Fame. Without a change in the rules, the Baseball Writers of America couldn't vote him in even if they wanted to, while the committees that take a second look at overlooked candidates would surely be reticent about altering the verdict of history.

Former Commissioner Bud Selig was adamant in his opposition to Jackson's reinstatement, but his successor, Rob Manfred, seems more amenable to recognizing Shoeless Joe.

Not reinstatement by any means. But baby steps nonetheless.

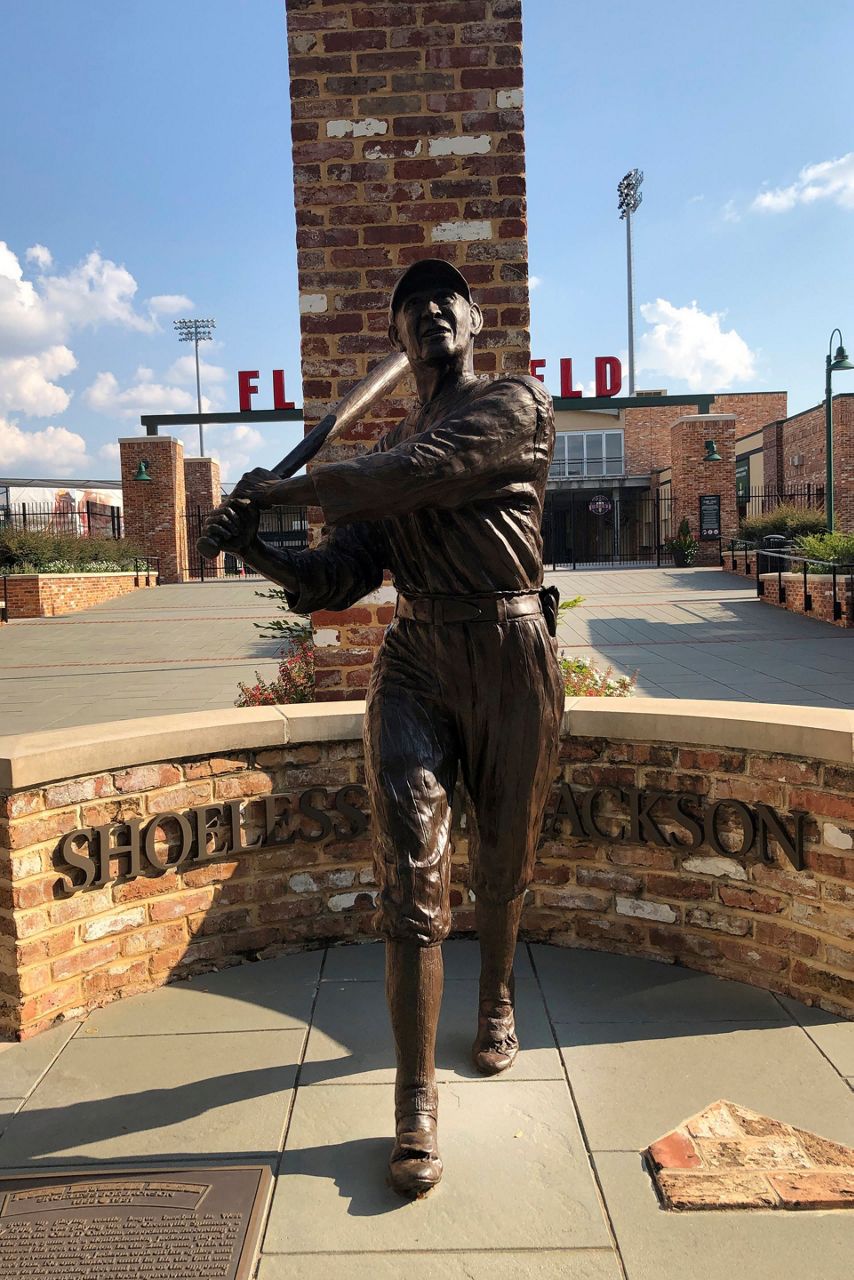

At Fluor Field, home of the South Atlantic League's Greenville Drive, they now have a statue of Jackson right outside one of the main gates and a large picture of him in an area known as Heritage Plaza. Next year, MLB will construct a temporary stadium in that Iowa cornfield made famous by "Field of Dreams," the movie that portrays the ghost of Shoeless Joe emerging from the tall stalks to take part in one more game with other long-gone players. The New York Yankees will play an actual regular-season game against ... the White Sox.

Jackson's team.

"There is a groundswell of support growing for Joe Jackson," Wallach insists. "We're going to make sure that name stays in the forefront of baseball history."

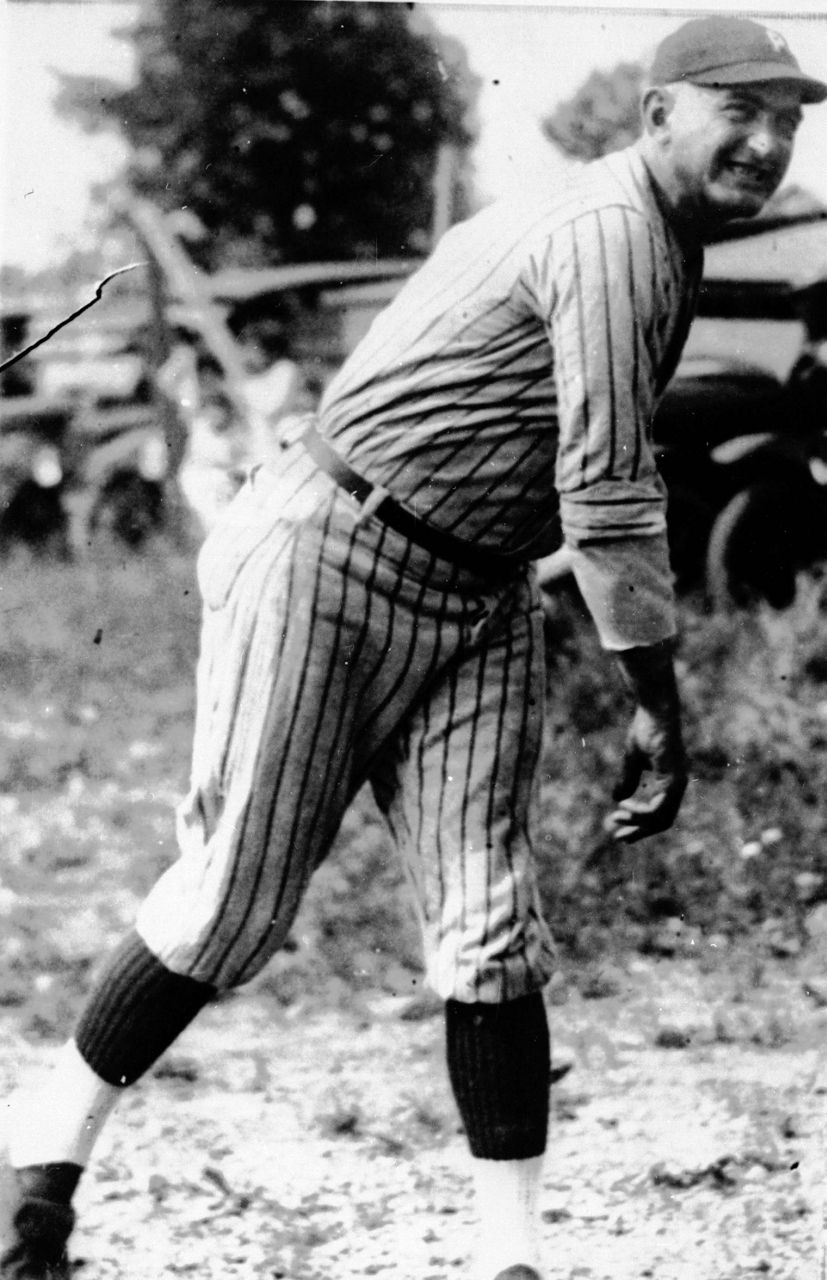

There is little doubt that Jackson was one of the game's greatest players.

He batted .408 one season and finished with the third-highest career average (.356), a number that now adorns the address of his museum — 356 Field St. He could also hit for power within the constraints of the dead ball, not to mention run, field and throw. Today, we'd call him a five-tool player.

"I want people to know what a wonderful ballplayer he was," Wallach says wistfully.

___

The Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum is run on a shoestring budget by a small group of faithful volunteers. The hours are skimpy. Saturdays only, from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

But bigger plans are in the works.

Wallach's son, Dan, will soon be moving from Chicago to run the museum full time, with an eye toward expanding both operating hours and its mission in the community. The museum will also be moving — literally, as workers take the entire house to a spot just up the street, clearing the way for a new development at its current (and actually second) location.

The home was brought in from its original spot three miles away to coincide with the opening of Fluor Field in 2006.

As part of this latest move, the museum will get a new gift shop — check out the "Reinstate Shoeless Joe Jackson" T-shirt — and open up more space for exhibits.

Shoeless Joe may never get into the Hall of Fame. But he deserves at least a mention in Cooperstown, some remembrance of his entire body of work and not just those eight infamous games a century ago.

"It's a tragic story," Wallach says. "But we have ways to fix tragedies."

Yes, we do.

Major League Baseball, say it's so.

Welcome back Shoeless Joe.

___

This story has been corrected to show that the first baseball commissioner's first name is spelled Kenesaw, not Kennesaw, Mountain Landis.

___

Paul Newberry is a sports columnist for The Associated Press. Write to him at pnewberry@ap.org or at www.twitter.com/pnewberry1963 His work can be found at https://apnews.com

___

More AP MLB: https://apnews.com/MLB and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports

Copyright 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.