When Josephine Bisono’s former landlord got tired of waiting on rent payments from OUR Florida, she decided to decline the funding and not renew Bisono’s lease for the following year.

What You Need To Know

- Many people are having issues with OUR Florida – tenants and landlords alike

- Florida's "pay to play" eviction law allows cases to move quickly, and some residents have been displaced before their assistance arrives

- In a letter to Treasury, the Department of Children and Families said it had committed 42% of its funds by Nov. 15

- ERA programs were supposed to have spent at least 65% of their allocations by Sept. 30, or risk losing remaining funds

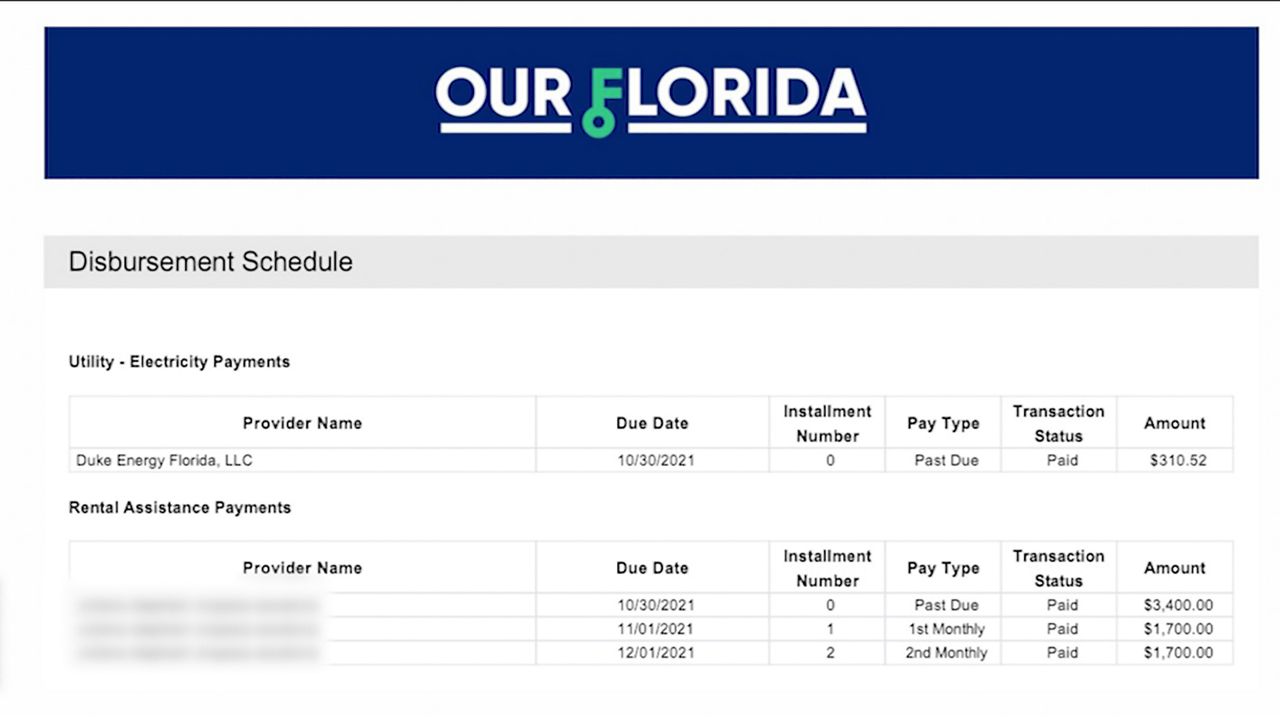

So Bisono was shocked when she learned OUR Florida — the state’s federally-funded relief program to help residents and businesses with unpaid rent and utility bills — paid out her former landlord a month after Bisono already lost her eviction case.

(Provided by Josephine Bisono)

“The whole idea for OUR Florida is to help people like us, and there’s many of us,” said Bisono, who is currently staying at a friend’s living room. “I’m very disappointed … they really didn’t do anything for me.”

Indeed, many Floridians are struggling to navigate the federally-funded program OUR Florida, which stands for Opportunities for Utilities and Rental Assistance. More than 1,300 people belong to a Facebook group created for users to share their experiences with the program, and while triumphant posts do occasionally appear, most are stories of sorrow and frustration, as landlords and tenants alike grapple with long wait times and inconsistent information from staff.

RELATED stories:

- Eviction bans push some small landlords out of the rental business

- Allowed, but not required: ERA confusion mounts for hotel residents in Central Florida

- Housing Experts: Emergency rental money is there, but some landlords don't want it

In the last week alone, dozens of people reached out to Spectrum News with complaints about OUR Florida, including some urgent cries for help from parents, disabled people and seniors at risk of imminently losing their housing.

“I feel (worse) now than when I applied and with less hope that this system for ‘emergency’ will do any good for me,” one father wrote in an email.

So far, OUR Florida has not accepted interview requests from Spectrum News, or provided an explanation for the significant delays so many applicants are experiencing.

‘Emergency’ rental assistance?

OUR Florida is federally funded, just like the hundreds of other emergency rental assistance programs (ERAPs) created in response to the coronavirus pandemic. The programs are administered at state and local levels; OUR Florida was contracted by Florida’s Department of Children and Families. They were supposed to help keep renters stably housed, and protect property owners from financial ruin during the coronavirus pandemic.

But for many renters and landlords alike, the funds have not served their intended “emergency” function at all. On the contrary, for many, ERA funds have moved at a sluggish pace, failing to protect people from housing instability and financial hardship.

For many Floridians, these were familiar challenges only exacerbated by the pandemic. For others, like Bisono — who said she previously earned a $95,000 salary working in hotel sales — it’s not so familiar.

“I’ve been filing income tax returns since I was 14 years old,” said Bisono, who’s originally from New York City. “I have never asked for a handout … I have paid taxes. All I wanted was for OUR Florida to come through and help me out.”

Bisono said before the pandemic hit, she was on top of her finances, even able to pay rent one or two months ahead at the condo where she used to live on the edge of Orange County.

She was furloughed, then laid off from the hotel where she used to work, and lived off unemployment and stimulus payments until those dried up this fall.

Bisono said she’s been applying for jobs nonstop. While she’s gotten close a couple of times, nothing has panned out yet. She said most postings advertise salaries $30,000 lower than what she earned in similar positions.

“I had an interview for five hours one day,” Bisono said the day before Thanksgiving. “I have so many ideas, and I’ve been doing this for 25 years, and I still don’t get hired.”

‘The whole program is chaos’

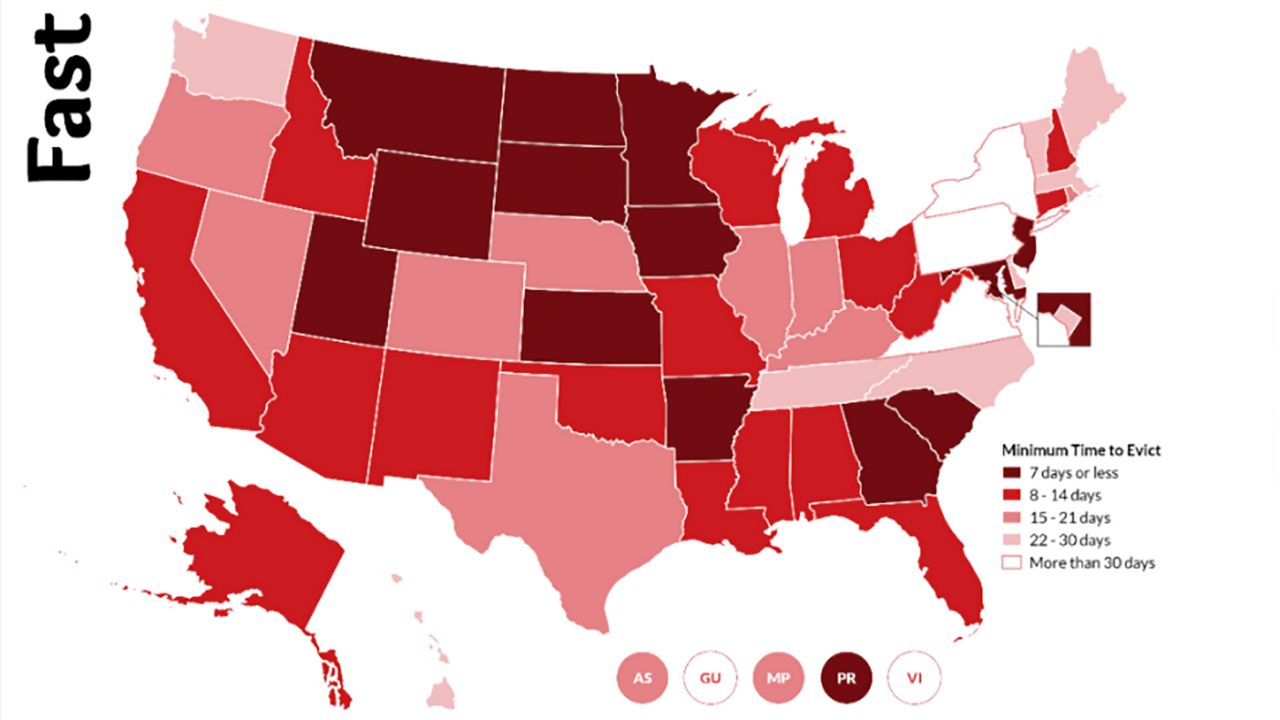

Tenants in Florida do not have much time to work with when they fall behind on rent. A recent Legal Services Corporation study found the eviction process to be “too fast” generally throughout the United States — but Florida’s is among the fastest, providing tenants only three business days to respond to a late notice before their eviction case can move to court.

In other jurisdictions like New York and Pennsylvania, tenants have 30 days to respond after their landlord notifies them they’re behind.

(Courtesy of Legal Services Corporation)

The LSC eviction study, completed per a Congress directive, called out Florida and Arkansas as “pay to play” states, where tenants forfeit their right to a court hearing if they cannot pay the full amount of back rent landlords claim they owe. Even then, without legal representation, very few tenants can win eviction cases for nonpayment of rent, according to attorney Jorge Acosta Palmer of Community Legal Services of Mid-Florida.

“The only thing putting money into the court registry does is give (tenants) a fighting chance to present their defenses,” Acosta Palmer said. “At that point, it’s up to the judge to decide.”

Acosta Palmer said when tenants do get a court date to plead their case, the biggest and most common mistake they make is admitting they were late on rent to begin with. That is exactly what Bisono did in her answer to the judge.

“I have always complied with the landlord and (paid) the rent, at times I will pay the rent ahead of time,” Bisono wrote. “At the moment, I am going through some hardship and I am behind the rent.”

In her answer, Bisono went on to raise what Acosta Palmer calls a “good faith” defense, which he and his legal aid colleagues encourage: she summarized the efforts she’d made to get OUR Florida assistance, explaining she’d applied the previous month. (Her landlord had, too, according to an email Bisono received from OUR Florida in mid-October.)

Josephine Bisono rides the SunRail to try and get back some rent money she paid into Orange County's court registry before being evicted. (Spectrum News 13/Molly Duerig)

Bisono’s application was approved, she explained to the judge — not just for the month she owed, but for three months of future rent, too. All Bisono’s landlord had to do was wait for the checks to arrive, Bisono wrote.

But waiting was not something Bisono’s landlord was willing to do.

It’s a frustration Jayne Rocco, a different landlord in Volusia County, can understand.

“Landlords cannot wait three and four months and get the runaround, not knowing if (the money’s) even coming in,” Rocco said. “They have to go ahead and evict these tenants.”

Rocco herself almost had one tenant removed recently, after weeks of battling OUR Florida for an update on her application status. At the last hour, Rocco said, the tenant was finally notified her assistance was approved, and Rocco dropped the eviction.

“The whole program is chaos,” said Rocco, who is still trying to get two other tenants’ approved payments, after weeks of failed attempts. “Nobody knows what’s going on … it’s really upsetting that you can’t get anybody (at OUR Florida) to respond to you.”

Rocco said she’s filed at least six complaints online with OUR Florida, but never got any confirmation those complaints were received.

Recently, the program finally mailed checks to Rocco’s tenant after weeks of confusion, even though Rocco requested to receive payments via direct deposit.

But the checks never arrived, and apparently cannot be traced. They were made out to Rocco’s LLC, not Rocco herself or her tenant. OUR Florida told Rocco it would take 90 days to reissue the checks.

“If the program worked right, it’s excellent,” Rocco said. “I don’t know why landlords wouldn’t want to work with it, because you’ve got guaranteed rent coming in on time, every month.”

“But it doesn’t work right,” Rocco said.

‘That’s our system’

The Treasury Department is required to reallocate “excess” funds from ERA programs that hadn’t committed at least 65% of their funds by Sept. 30. By that point, Florida had only committed 21% of the funds available through OUR Florida, according to a National Low Income Housing Coalition report.

Programs that weren’t spending quickly enough had to send Treasury a program improvement plan by Nov. 15. By that point, Florida had distributed 42% of its ERA1 funding, according to a letter to Treasury by DCF. Although that figure was still below the 65% required to be committed by Sept. 30, the state requested no funds be reallocated from its program.

Despite her best efforts, Bisono lost her case and was ultimately evicted on Dec. 3 — two days after she was notified OUR Florida had cut two checks for her landlord, and approved a third. Since then, the status of the third payment has also changed from “approved” to “paid.”

In total, records show OUR Florida has paid out Bisono’s landlord for $6,800. That includes rent for the month of December.

“There you go. That’s our system,” Bisono said.

history_museum)