ORLANDO, Fla. — When Mark Rawls finally got off the streets of Orlando after nearly fifteen years, he swore he’d never go back to being homeless. The 54-year-old Navy veteran credits therapy and medication for helping him recognize and begin to heal from his previously undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance abuse issues.

But then, just two months ago, Rawls relapsed – on drugs, and on homelessness.

What You Need To Know

- Homeless Services Network: Vets make up almost 17% of homeless or near-homeless people

- Vast majority of homeless veterans are men

- PREVIOUS STORIES:

“It was comfortable for me,” Rawls said. “Mentally, [being homeless] was comfortable. And it was something that I did consistently for 15 years. So I tried to revert back to that, and I found out that it wasn’t so comfortable at all.”

Veterans make up almost 17% of all people who have experienced or come close to experiencing homelessness during the last 12 months in Orange, Osceola and Seminole counties, according to an estimate from The Homeless Services Network (HSN) of Central Florida. The vast majority of those veterans are men.

Just like in Rawls’s case, untreated mental health and substance abuse issues are major contributing factors to homelessness among veterans, according to Stefanie Mohl, the homeless program supervisor at Orlando’s Veterans Affairs Department. Veterans’s psychological conditions may lead to behavioral issues, which in turn may lead to legal or financial difficulties for the veteran.

“One of the biggest challenges that we encounter is the housing market in itself,” Mohl said. “Very few [veterans] are able to access affordable rental properties, and unfortunately, we have a fairly limited number of landlords and property managers who are willing to make that investment in our veterans with some more challenging legal and credit histories.”

The process of searching for safe, affordable housing can frustrate some veterans who are already battling their own mental health – like Rawls, who said he temporarily “regressed” back to the homeless lifestyle he’d previously lived for years. But this time around, it only took a couple months of sleeping in a parking garage in downtown Orlando for Rawls to decide he deserved better. Now, he’s staying in an extended stay hotel south of the city, working the same kinds of construction gigs he said he continued to pick up, even while spending nights in that garage.

“Homelessness is a state of mind, more than anything else in America,” Rawls said, sitting on the cement bench of the parking garage he used to sleep on.

Rawls credits the VA for providing the healthcare necessary for him to gain deeper self-awareness and coping skills for his PTSD.

“I'm fortunate to be able to have the VA to kind of guide me through my mental issues,” Rawls said.

“Just think of a person who doesn’t have access to any mental health [care], and they have no idea why they’re doing the things that they’re doing,” Rawls said. “It becomes mechanical after awhile.”

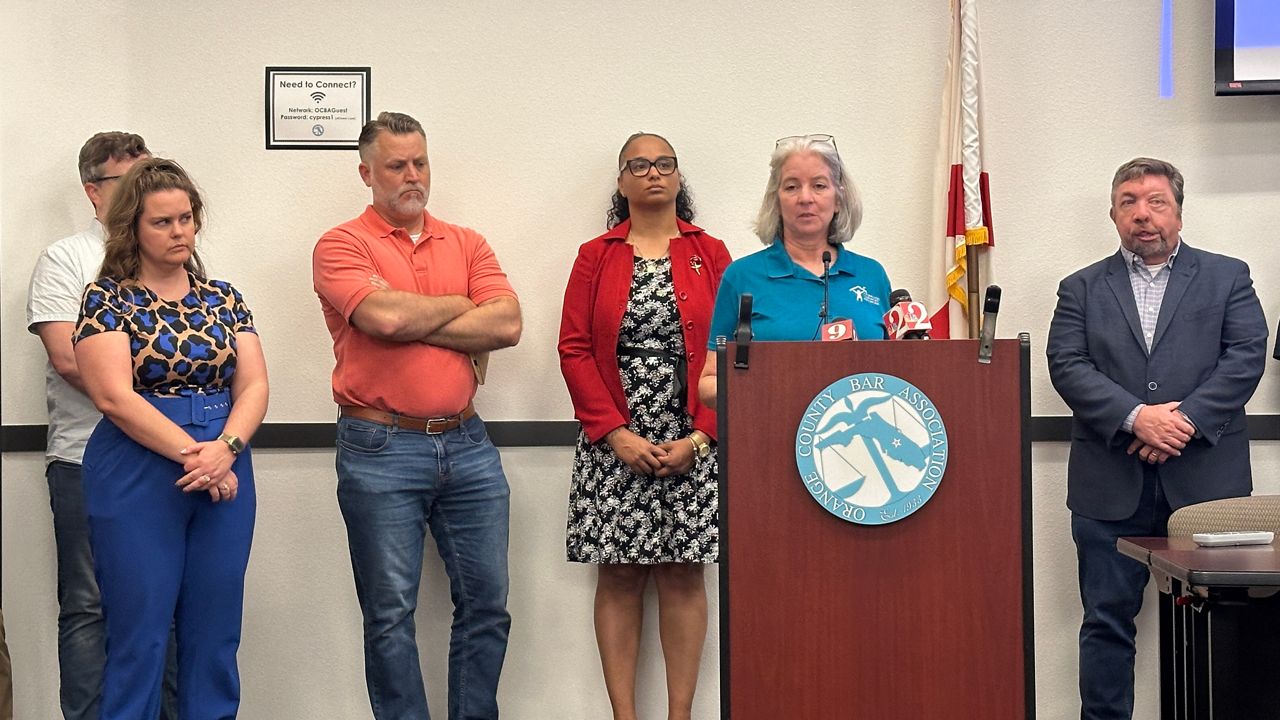

Many veterans aren’t eligible for the same kind of healthcare and assistance Rawls receives from the VA. To be eligible a veteran must have completed a certain amount of active service days, depending on the era and conflict they served in, according to Martha Are, CEO of the HSN of Central Florida.

Additionally, many veterans who have been dishonorably discharged from the military are ineligible for VA healthcare. Often – not always – those veterans’ behavioral issues may have been due to previously undiagnosed mental health conditions, Area said.

“Someone can get discharged and then we find out three years later they were mentally ill,” Are said, citing schizophrenia as one condition that often doesn’t present itself in an individual until they reach their twenties.

Even with assistance from the VA or other support systems, personal healing is hard work. Army veteran Herbert Jones, 66, has several physical disabilities – and seven Purple Hearts from basic training, he said.

When his back gave out earlier this year, Jones said he got behind on his rent. Then, the coronavirus pandemic hit. Eventually, in August, he called the VA for help. They helped him get find The Recovery House, in Sanford. Jones stayed there while the VA helped him identify a more permanent living situation for him – which they did, about a month ago. Jones has been living in a HUD apartment ever since.

“You’ve gotta put something in to get something out,” Jones said of his experience with the VA. “You have to talk to people, you have to communicate … it’s a two-way street.”

With Jones’s social security and food stamps back on track, he says he can pay his bills and have a few dollars left.

Jones was proactive about seeking help from the VA. That take-charge mindset will be crucial to Rawls’s continued success, too. Back at the extended stay hotel, Rawls checks in with a doctor from the VA on the phone, who ensures his prescriptions are up to date and he has a therapy plan going forward.

Mohls said often, by the time veterans get to the VA’s homeless services program, they are already estranged from most of their family. That’s not the case for Rawls, who said he speaks to each of his four daughters on a regular basis.

Even with that familial support and his self-awareness, Rawls relapsed. But this time, he feels his recovery from homeless will be permanent.

“I can have a productive, comfortable life without looking back. I’ve learned the only thing to do now is to look forward,” Rawls said.

Molly Duerig is a Report for America corps member who is covering affordable housing for Spectrum News 13. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

)