TOKYO (AP) — In the darkest days of the pandemic, Evita Griskenas was stuck practicing in her parents’ Illinois basement, occasionally breaking lightbulbs as she tossed clubs and hoops through the air and cartwheeled to catch them.

A song she had never heard started playing. Griskenas, a rhythmic gymnast, doesn’t so much hear music as she sees it: melodies become hoops spinning across the floor; drumbeats bounce like balls. This song felt wild, like ribbons whipping in wind.

Often the forgotten genre of Olympic gymnastics, her sport is like combining its more famous cousin, the artistic gymnastics practiced by superstars like Simone Biles and Sunisa Lee, with ballet and a circus. Gymnasts dance as they throw and catch items — hoops, balls, ribbons, a pair of clubs — bending and twisting across a carpet so quickly it’s often impossible for the untrained eye to understand its intricacy.

In her parents’ basement, Griskenas danced to this strange song and as it ended with a thunderous saw of a violin, she struck a pose.

“This is an Olympic quality song,” she remembers thinking: “I can imagine myself in Tokyo, hearing this as the final du-dun!”

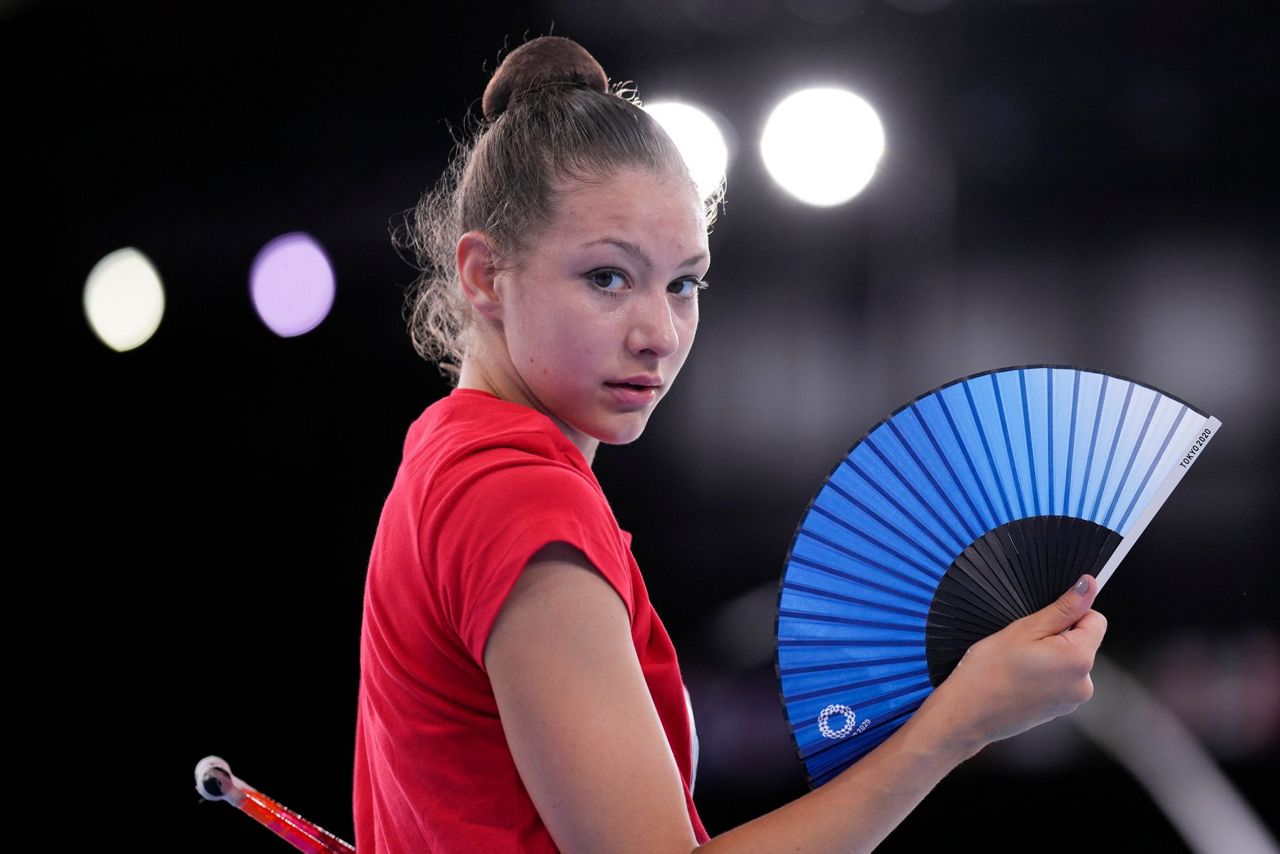

Now when she thinks of that moment, she gets emotional because it will soon come true: Griskenas is part of the first full rhythmic gymnastics team the United States has ever sent to an Olympics. She is one of two individual performers to qualify to compete this weekend, along with a five-woman team that performs perfectly in synch. In this sport dominated since its inception by Russia, America’s rhythmic gymnasts say they hope their increased presence in Tokyo could mark a turning point for the sport back home, where they are often dismissed as ribbon twirlers and hula hoopers.

“We’re out here making history,” said Lili Mizuno, a member of the five-women team, who says there’s so much packed into their performances, she believes if people see it they will fall in love. “There’s so much going on every single second. You could put the video in slow motion and still have so much to look at.”

Twirling the satin ribbon — nearly 20 feet long — requires keeping their wrists in constant motion, for instance. They roll the balls and hoops around their bodies. They launch the clubs into the air then acrobat to the opposite side of the 40-foot competition floor to catch them the precise moment they fall. Point deductions are taken for a stray throw, a wayward ribbon, a missed catch.

It is intended to look effortless, but to make it so, they trained all day every day for months.

“We feel like we deserve more spotlight than we get,” said Camilla Feeley, a member of the team. “People in the U.S. just don’t understand what this sport is.”

Feeley calls herself the hoop-bearer because she likes to carry all six hoops when they travel. As they took off for Tokyo, she said, a flight attendant tried to stop her.

“We’re heading to the Olympics, I need this by my side the whole time,” Feeley told the attendant. She thinks of the hoops as like her children and feels incomplete without the weight of them in her hand, so she bargains to get them on board: “They’re just confused. I’m sure it’s not every day that they have rhythmic gymnasts board their plane.”

Most of their equipment must be ordered from overseas. Their toe shoes — specific to rhythmic gymnastics because the toes are covered but heel left bare — cost about $30 a pair, and they can go through them in a week or two, depending on the roughness of the competition carpet. Sometimes to avoid buying new ones, they patch them up with medical tape.

Their counterparts in other countries are often shocked to learn they don’t get paid. They receive some support, but nowhere close to covering the cost of training, travel and equipment.

“Don’t even get me started about the leotards,” said Mizuno. They are mostly made by seamstresses in Russia, where rhythmic gymnastics is a wildly popular sport. They are so covered in crystals they can weigh as much as 10 pounds and cost thousands of dollars.

Their families have made extraordinary sacrifices for them to pursue this sport.

Mizuno’s parents and two brothers moved with her from California to Illinois so she could train at the best gym in the country. Sometimes they couldn’t afford the cost and her mother would spend months sewing toe shoes and leotards so they wouldn’t have to buy them from Russia. Sometimes Mizuno wore her teammate’s hand-me-downs.

Feeley's mother also moved with her to Illinois from Maryland, so she could train at the same gym.

American rhythmic gymnasts often go to learn in Russia, where the sport has a robust infrastructure absent in the U.S.

“In the U.S., we’re slowly, gradually building that,” said veteran Laura Zeng, who competed in the 2016 Games and is returning for Tokyo. “But it takes time and money, so we go to Russia to train, to learn from them.”

She was there last spring, about to head into the gym when they announced the U.S. was closing its border because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and she had to find a flight and head home right away.

“Everyone was on their tippy toes, not knowing what was going to happen next,” she said. For three months, they couldn’t go to the gym. They tried to train on Zoom in their basements and living rooms. It’s hard to hurl clubs in basements and bedrooms; lightbulbs were broken, months of training lost.

But rhythmic gymnasts are used to being adaptable, Zeng said: for example they have to factor the strength of arena’s air conditioners into their routines, because a hard-blowing system can derail the flutter of their ribbons.

“That’s a good metaphor for the pandemic: everything was just kind of flopping around and we had to go with the flow,” Zeng said.

Their sport is emotional, many describe it as telling a story to the audience and they feed off how the crowd absorbs it. But there won’t be one in Tokyo.

“I don’t think anyone will have any trouble getting that adrenaline up because of what it means to be an Olympian,” Zeng said. “Everyone knows what that honor is, so we’re all carrying that beautiful knowledge on our shoulders. So when we go out there will have that power with us.”

Many of the American rhythmic gymnasts don’t sugarcoat their chance at winning.

“Definitely probably not,” laughed Mizuno. The team barely qualified for the Olympics, squeaking into the lineup by a tiny margin. “It’s almost a miracle that we are able to be here at this moment right now.”

Both the individual and group performers will compete at qualification Friday and Saturday morning, followed by the individual final Saturday evening and the group final Sunday. The Russians remain seemingly unbeatable, and until the United States invests more in their sport, they’re unlikely to reach a podium, many of America's athletes acknowledged.

But they’re determined to make the most of it to gin up interest in rhythmic gymnastics, which is changing in ways they think could appeal to an American audience.

It has historically been performed to classical music; its origin involved a live pianist accompanying the gymnast from the sidelines. But the rules have loosened to allow songs with words, and some gymnasts are incorporating genres like hip hop, techno and mainstream pop songs.

One of the group's performances this year will be to a techno remix of Bon Jovi’s “It’s my Life” — an unapologetically American song, Mizuno said.

They dream of a day when rhythmic gymnastics is well-known enough in the United States, people on planes stop mistaking their rubber-tipped clubs for bowling pins.

“The U.S. has finally started shouldering our way in,” Griskenas said, and laughed. “Or maybe I should use a rhythmic gymnastics pun: we’re clubbing our way in. Here we come.”

__

More AP Olympics: https://apnews.com/hub/2020-tokyo-olympics and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.