Since the modern satellite era began in the 1960s, advancements in weather observations and forecasting have become exponential.

Today, NASA’s satellites can take high-resolution images of hurricanes as frequently as every 30 seconds. Hurricane hunters routinely fly planes into storms to take measurements. We also have weather models and computers that help forecast a storm’s path and intensity.

All this technology makes tracking storms a lot easier. But how did meteorologists track storms and create forecasts before weather satellites and computers? It wasn’t so easy.

Before modern weather technology, hurricanes were often a surprise to people who lived on the coast. Can you imagine a major hurricane arriving with no warning?

It wasn’t as simple as looking at a satellite picture of the Atlantic Ocean in the 1800s and earlier. Before plane travel, unless a storm affected a populated land area or encountered an unlucky ship in the Atlantic, storms could go unnoticed.

Spectrum News Chief Meteorologist Gary Stephenson says experienced sailors could recognize the signs of a big storm as early as the 1500s. “Christopher Columbus encountered a hurricane in 1502. He saw signs of the storm developing and approaching, and sought shelter for his fleet before the storm hit,” he added.

Eventually, in the 1800s, the United States established a network of weather observation sites. The government set up the first formal hurricane warning service ever in Cuba in the 1870s.

The understanding of pressure systems and fronts evolved in the late 1800s thanks to daily observations. Stephenson says that gave forecasters an idea of weather patterns and how tropical systems might move and the tracks they would take.

Eventually, in the early 1900s, wireless communications became more reliable. “Ships could report storm position and information in real time when they encountered a storm. The same occurred if a storm struck land,” said Stephenson.

Ships utilized the same communication system that was used on land. If a storm made landfall on an island or moved inland, that information could be passed along. It allowed broadened storm warnings for extensive areas that a storm might affect.

By 1935, there were regional offices in Jacksonville, Fla., Washington, D.C., San Juan, Puerto Rico and New Orleans, La. The offices comprised the nation’s first hurricane warning program. Even with all the improvements in the early 1900s, hurricane forecasting was far from perfect.

In 1938, a storm known as the ‘Great New England Hurricane’ or the ‘Long Island Express Hurricane’ made landfall in the Northeast. It made landfall on Long Island, N.Y. and moved across New England, estimated to have made landfall as a category 3 hurricane.

As it was approaching the Northeast U.S., forecasters knew that there was a storm in the Atlantic, but had very few reports of its exact strength and location. It turned out that it was much stronger and larger than anyone had known.

Advisories and warnings were too late, coming in as the major hurricane was making landfall. It ended up killing over 500 people and damaging and destroying over 50,000 homes.

Weather technology continued to blossom in the mid-1900s.

As air travel became more reliable in the 40s and 50s, the hurricane hunters were born. Aircraft would fly across the Atlantic during hurricane season looking for potential tropical systems.

Storm naming began in 1947, and female names were introduced in 1953. In 1956, the National Hurricane Center that we’re familiar with today became established in Miami, Fla.

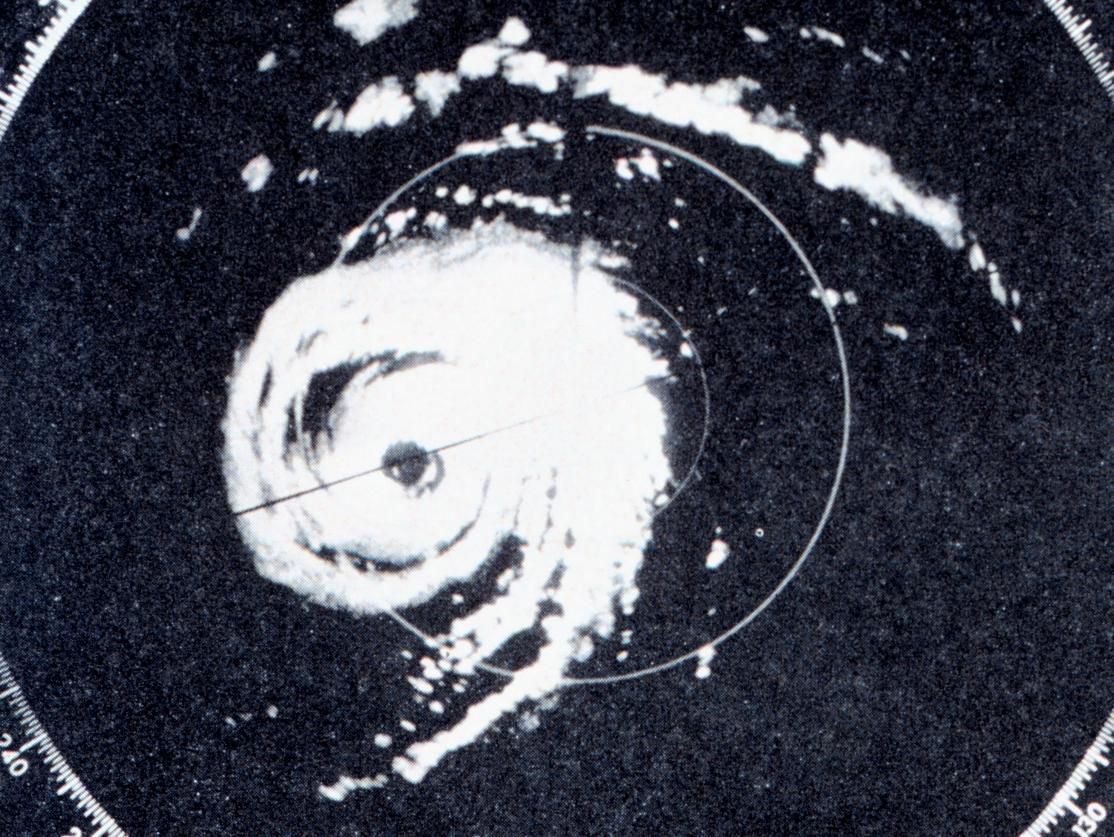

In 1959, the U.S. put the first weather surveillance radar into operation in Miami. Radars weren’t nearly as advanced as they are today, but they became another crucial tool in tracking storms and hurricanes as they neared land.

Storm track and position forecasts continued to extend further into the future during the 1960s as hurricane research improved. Computer models were built to simulate hurricane tracks for the first time.

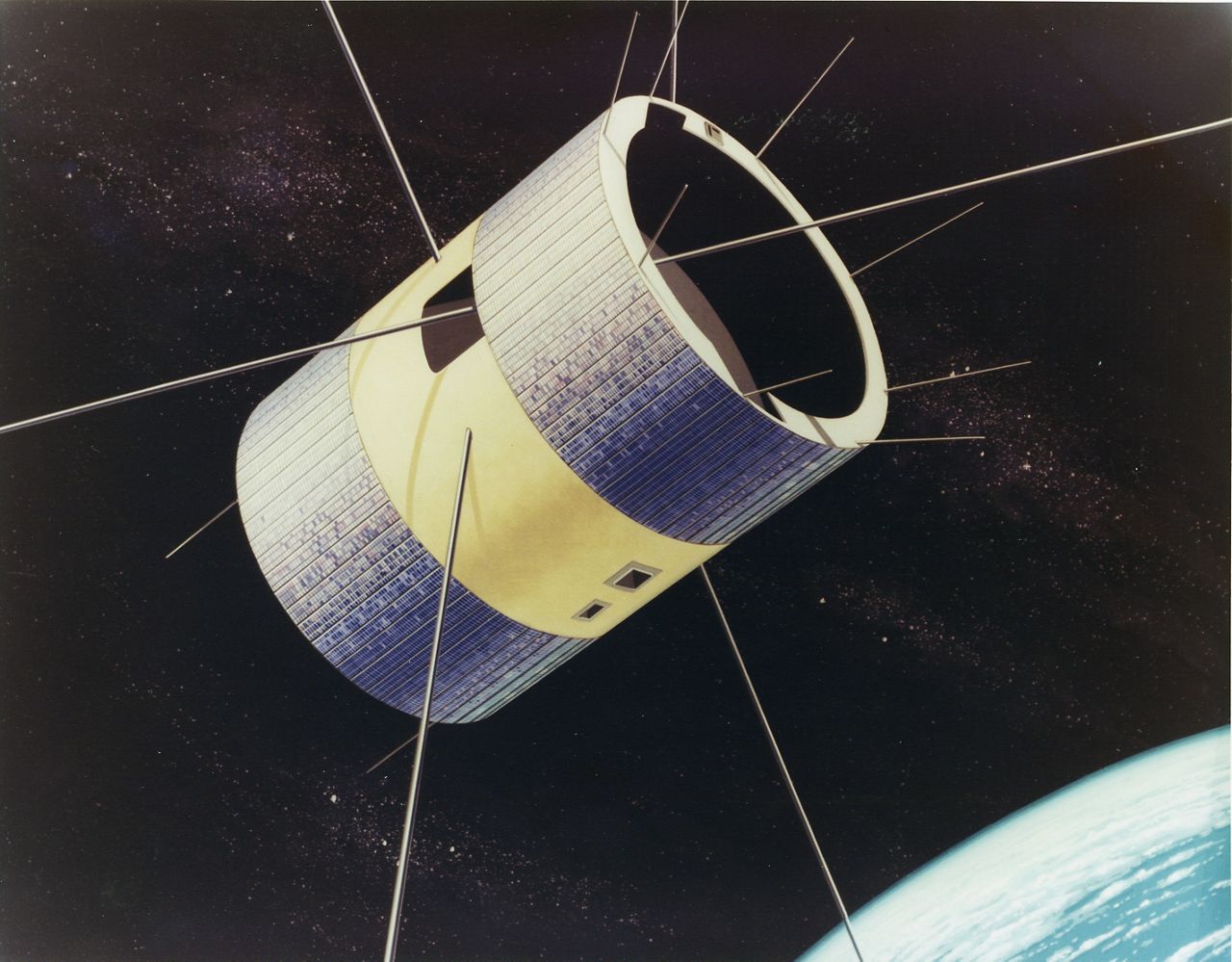

The 1960s became a pivotal turning point in the world of hurricane forecasting and meteorology. The first geostationary satellite for weather purposes was launched into orbit in Dec. 1966., marking the beginning of the modern-day satellite era.

The 1967 Atlantic hurricane season was the first in the modern-day satellite era.

ATS-1 was the first geostationary satellite for weather, launched in Dec. 1966. It was fully operational for the 1967 hurricane season, able to send images back to earth of the western hemisphere up to every 30 minutes.

The satellite was in a fixed position over the western hemisphere. The pictures allowed meteorologists to see changes in cloud cover over the same area, making identifying and tracking storms a lot easier.

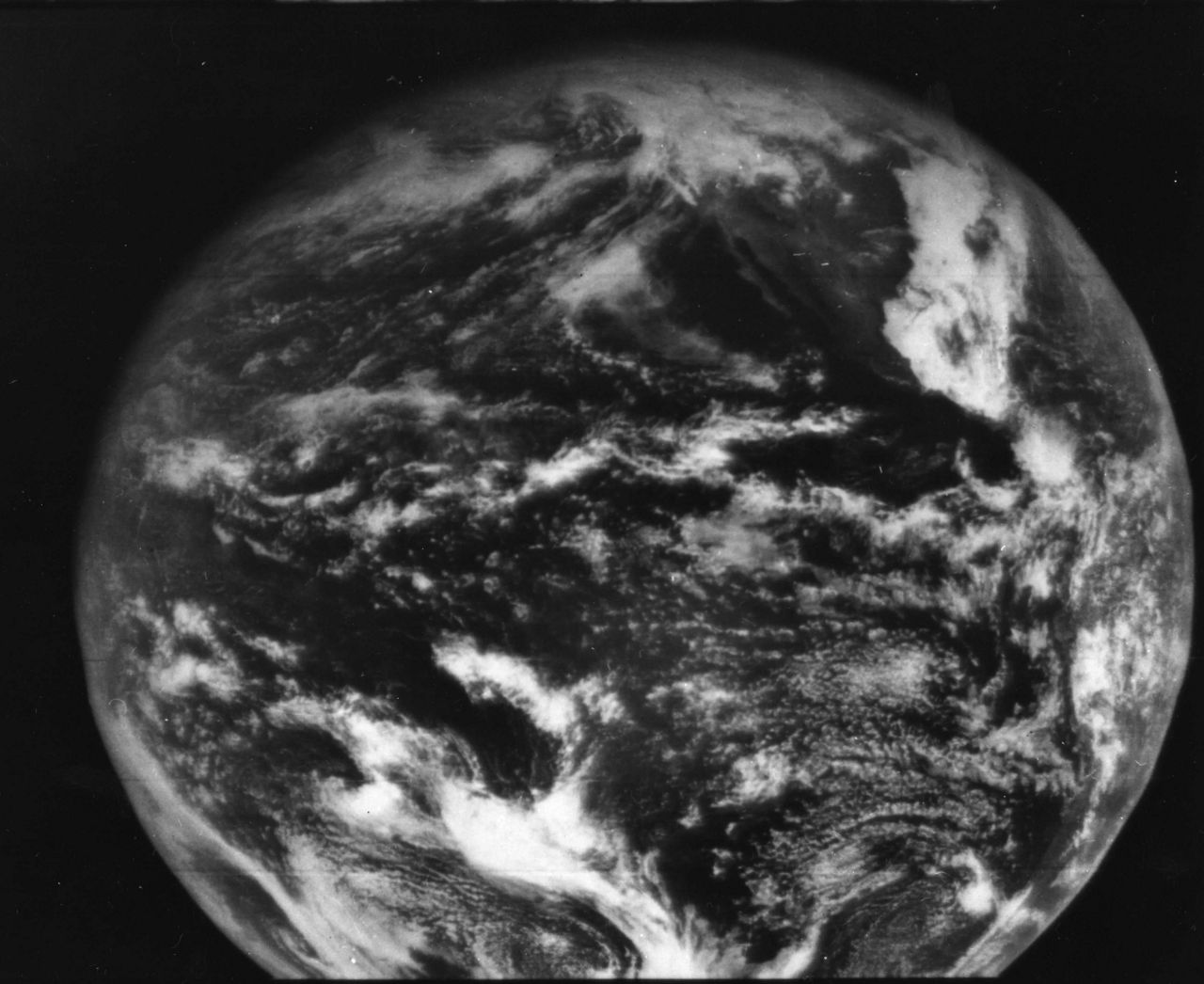

Through the late 1900s, computer power, weather observations and satellite data all increased. As computers became faster and more powerful, so did weather models.

Today, meteorologists have an abundance of tools we can use to predict hurricanes days in advance with more accuracy than ever before. Models can warn meteorologists before a storm has even developed of where atmospheric conditions are most favorable.

Weather satellites today can take high-resolution pictures of storms up to every 30 seconds, tracking every movement and wobble. In addition to taking pictures of what they look like from space, satellites can detect lightning activity, infrared radiation to determine temperatures and much more.

Doppler radars around the country in the Caribbean can also show us when rain and storms in a hurricane’s outer bands move in.

Our extensive network of weather observation sites and hurricane hunter data provide us with real-time wind speed and storm strength estimates.

So, next time you see a hurricane’s ‘cone of uncertainty’ and wonder why the forecast isn’t always perfect, remember how far it’s come in such a short time.

Our team of meteorologists dive deep into the science of weather and break down timely weather data and information. To view more weather and climate stories, check out our weather blogs section.