This story is part of Spectrum News’ initiative, “Street Level,” which explores Florida through the history and culture of specific streets and the people who live there. You can watch part two of Street Level: Division Avenue here.

It’s been described by some as a dividing lane between cultures and a nod to a painful period in U.S. history.

Others view the street as an opportunity for discussion, positing that changing its name could help to foster healing.

Still, more than a century after Division Avenue, once called Division Street, was laid out, it remains. As does the community which sprang from Division, Parramore. It originally took on the name of Orlando’s 14th mayor, a white, former confederate captain named James B. Parramore, and the name has stuck to this day.

Division forms the eastern boundary of the Parramore community, and is a physical reminder of the neighborhood’s segregated past.

“This was the Black community,” said Elizabeth Thompson, the executive director of the Wells’Built Museum of African American History and Culture. “Division Avenue was the dividing line between Black Orlando and white Orlando at that time.”

Thompson spends her days giving tours of the museum. The nearly century-old, brick building, located along South Street in downtown Orlando, is rife with history: artifacts, memorabilia, paintings, and posters fill every wall and corner.

The most telling details are the names in a ledger — like B.B. King, Ella Fitzgerald and Ray Charles. They provide clues as to who played for African American audiences there decades ago, as well as who stayed at the 20-room hotel.

According to state historian Ben Brotemarkle, Division Street is listed on maps from the late 1800s and early 1900s, mirroring the practice of many communities throughout the U.S. in which streets called Division denoted a dividing line between the Black neighborhoods and the predominantly white areas.

In Orlando, the divide was later reinforced by highways, like I-4 and State Road 408.

Thriving Community, Target Attacks

Yet the Parramore community, in which the hotel and casino were located, grew up simultaneously with the downtown Orlando area. It was vibrant and thriving in the early part of the 20th century, as Blacks carved out a community of their own filled with teachers, bankers, lawyers, doctors, and other professionals.

Photo courtesy: Florida Historical Society

One prominent community leader was Dr. William M. Wells, who set up his medical practice in Orlando and built the Wells‘Built hotel in 1926. It was penned into the Green Book as a safe haven for African-American travelers.

Next door, his bustling South Street Casino was part of the Chitlin’ circuit: a collection of venues which featured Black singers, musicians, comedians, and other performers during a time when much of the country was segregated.

“If they wanted to perform for an African American audience, they were going to do it at the South Street Casino,” Thompson said. “It was not for gambling, but it was an entertainment venue, it was a performance hall. It was a place you could get dinner and celebrate birthdays. And so it was an important part of the community in that way.”

Folks would “stroll,” putting on splendid outfits and strolling down Church Street, South Street, and Division Avenue, showing off their finery until they went into the Casino to hear the band.

“They had a great marketing strategy. What they would do was, as the band was warming up, they would let the patrons come in and listen. And the good dancers would be tapping their foot. They'd be listening,” said Brotemarkle, continuing, “And once they showed that these people were into the music, then they'd make everybody leave and pay to come back in.”

The Casino was bustling, and Wells’s hotel provided a respite for travelers and performers alike.

“You knew you could be welcome as an African-American patronizer or African-American customer. You knew that this hotel was going to be able to provide you a place to stay. And you knew that you could come into these businesses and that your dollar, your spending, would be appreciated and it would be welcome,” Thompson said.

But it was also a time of great strife. For the decades in which Orlando’s African-American population was relegated to the west side of Division, the community endured periods of intense harassment and violence.

“While you don't think of civil rights in Florida, all of that did happen here. In fact, per capita, there were more lynchings in Florida than any other state,” Brotemarkle said. “Right in downtown Orlando, there was a lynching of July Perry, and his town of Ocoee was burnt to the ground when he tried to vote in the 1920s.”

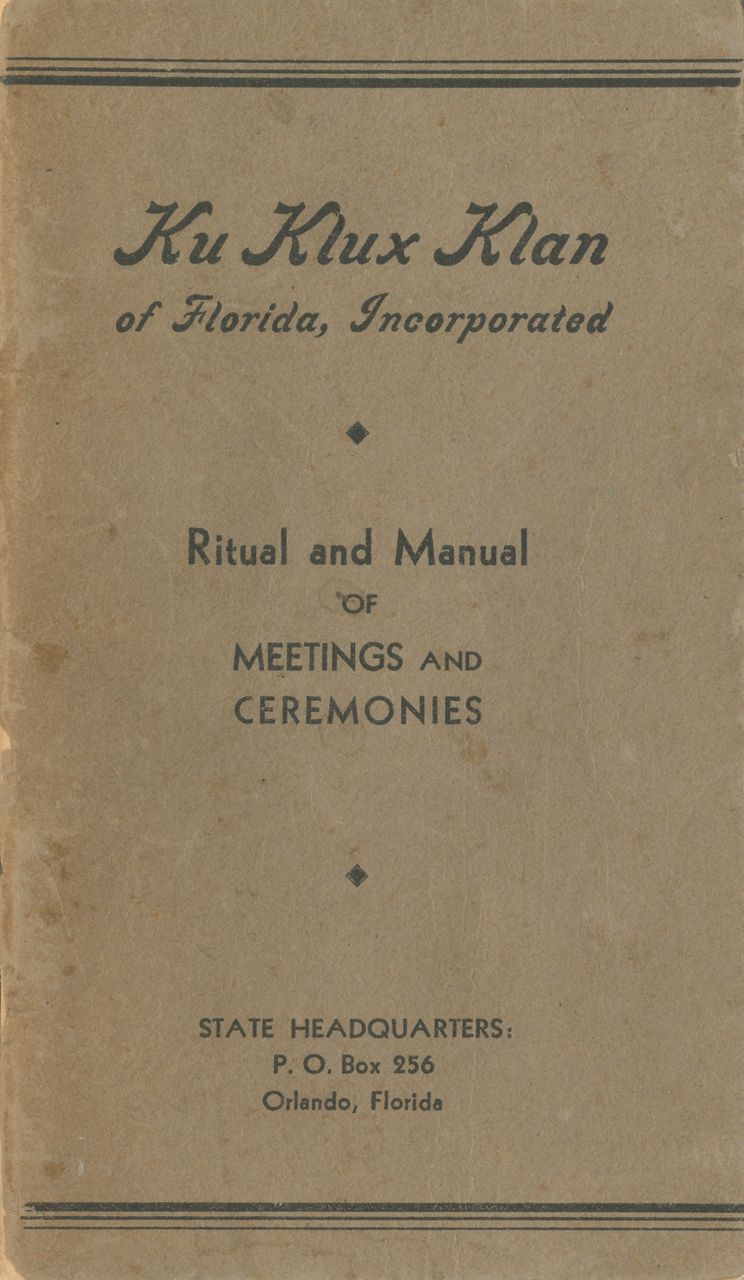

The massacre was preceded by an uptick in racism in the area, resulting from more African-American residents registering to vote. The Ku Klux Klan experienced a revival. Their marches, like through downtown Orlando along Orange Avenue, were meant to send a clear message to Black citizens.

Photo credit: Orange County Regional History Center

“There were bombings. There was an ice cream stand that refused to add a separate window for Black people. It was bombed and destroyed,” Brotemarkle said.

But Brotemarkle also noted the change that happened within the Parramore community in the 1960s, calling it an unintended consequence of desegregation.

“As civil rights laws were passed and people could move anywhere they wanted to, a lot of the community leaders that provided the infrastructure for the Parramore neighborhood moved out. And so in the latter half of the 20th century, the community went into a period of economic and social decline,” he said.

Decades later, the music had stopped. The South Street Casino fell into disrepair and the building was demolished. The Wells’Built Hotel next door, boarded up and abandoned, was headed towards the same fate.

“In the 1990s, I remember walking into the Wells'Built Hotel. There were crack pipes and obvious signs of drug use and homeless people having inhabited there,” Brotemarkle said. “There was a hole in the ceiling, where you could look up into the abandoned part that had been the hotel from what had been storefronts down in the bottom. It was in danger of being torn down.”

Preserving History

State Representative Geraldine Thompson, who is Elizabeth Thompson’s mother, couldn’t let that happen. While working at Valencia College on an oral history project, she began thinking about a repository where people could access meaningful historical items. That’s when the idea took shape in the late 1990s.

Unfazed by others writing off Parramore as blighted, she cobbled together donations to save Wells’s home and fashion a museum in the former hotel.

“All across the country, we see communities like Parramore disappearing. We see the physical evidence of the contributions of African-Americans disappearing,” she explained. “There was a vacuum in terms of people who saw the value of Parramore, I viewed it as a historic district and I view it that way today. One that should be preserved.”

But the discussion over how to honor a hurtful past while still marching forward continues today.

For more on Parramore and the future of its residents check out Part 2 of Street Level: Division Avenue.