KENNEDY SPACE CENTER — NASA's Monday launch attempt for the Artemis I mission has been scrubbed, but launch officials said a Friday launch is "still in play."

Multiple issues, including an engine bleed, resulted in Monday's Artemis I launch to be postponed.

What You Need To Know

- Monday's launch scrubbed

- Engine bleed postpones Monday's launch

- RELATED coverage:

A bent valve and an engine that would not reach the proper temperature also were factors, NASA officials said at a press conference later in the day. Weather officials also alerted possible rain in the area at the original launch time of 8:33 a.m. EDT, and lightning could have been a concern later in the launch window, officials said. All those factors led officials to determine it was best to call off the launch attempt Monday, they said.

NASA crews were working to gather data to work through the issues but officials said they would not know for sure whether they would make another attempt Friday until they had more of an opportunity to review that information.

“It’s just illustrative that this is a very complicated machine, a very complicated system and all those things have to work," NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said after the launch attempt was scrubbed. "And you don’t want to light the candle until it’s ready to go.”

Vice President Kamala Harris was on hand to see the launch but said she understood why it needed to be put off.

While we hoped to see the launch of Artemis I today, the attempt provided valuable data as we test the most powerful rocket in history. Our commitment to the Artemis Program remains firm, and we will return to the moon.

— Vice President Kamala Harris (@VP) August 29, 2022

Derrol Nail, of NASA’s communications team, said early Monday that officials got a warning that there was a “higher than acceptable” amount of liquid hydrogen in an area that covers the connections into the rocket. These sensors are designed to go off if any potential leaks are detected, Nail added.

The core stage liquid oxygen had a higher percentage of being filled than the core stage liquid hydrogen, said Nail, who added that there was a fast fill for both.

He said a liquid hydrogen line got a bit too warm during a fast fill but teams cooled the line.

In an update, NASA stated, "Teams continue to troubleshoot a (potential) liquid hydrogen leak at the mating interface with the core stage. After manually chilling down the liquid hydrogen as part of troubleshooting efforts, they are in fast fill operations."

The Space Launch System rocket will have 730,000 gallons of super-cooled liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen before liftoff.

Back in June, it was discovered that a collet — which is found inside the wall of the rocket’s engine section and holds an umbilical plate on — had some loose fasteners during a wet dress rehearsal, but it was fixed.

Due to storms during the overnight and the hydrogen leak, Nail announced a delay early, but it was not initially postponed.

NASA’s Space Launch System rocket originally was scheduled for an 8:33 a.m. EDT liftoff but had a two-hour launch window to send the Orion spacecraft from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Pad 39B on a 42-day mission to the moon and back.

NASA has two backup dates: Sept. 2 and Sept. 5.

“It’s just part of the space business, particularly a test flight," Nelson said. "We are stressing and testing this rocket and spacecraft in a way that you would never do it with a human crew on board. That’s the purpose of a test flight.

“They’re taking an opportunity while that vehicle is still fueled up to work this problem…and they’ll get to the bottom of it. They’ll get it fixed, and then we’ll fly.”

Mission specs:

- Space Launch System rocket: 322 feet tall

- Rocket fuel: 730,000 gallons of super-cooled liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen

- Orion: 10 feet, 11 inches tall and 16.5 feet in diameter

- Mission Duration: 42 days, 3 hours, 20 minutes

- Total mission distance: About 1.3 million miles

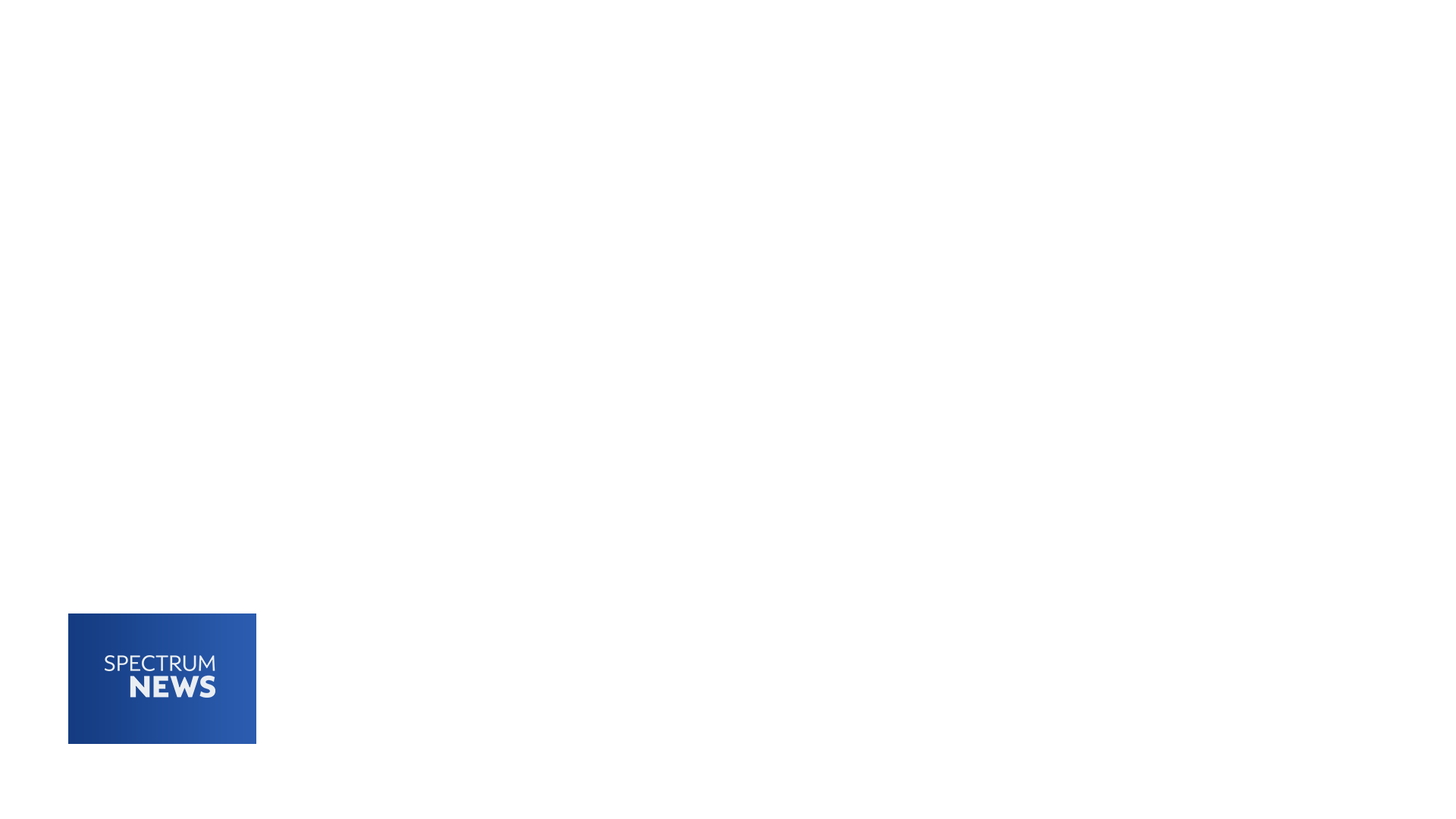

Understanding Artemis I mission

The Artemis program has three missions: Artemis I, Artemis II and Artemis III.

Artemis I is an uncrewed test flight that is designed to provide NASA with information that will be utilized for the two later missions.

Some of the tests that the Artemis I mission will conduct are: getting to the moon, orbiting the Earth’s lunar sister and returning home to test its heat shields and parachutes — because eventually astronauts will be in an Orion capsule and they will want a soft landing.

Once Orion is launched, it will orbit the Earth to gather enough speed to break free from the planet's gravitational pull and head to the moon. But to do that, Orion will use its own rockets (called the interim cryogenic propulsion stage, which is a modified United Launch Alliance’s Delta cryogenic second stage).

As Orion undertakes its days-long journey to the moon, NASA engineers will evaluate the spacecraft’s systems to make sure things are operating as expected.

While NASA is calling the Artemis I mission uncrewed, in the strictest technical sense, that is not entirely accurate. Cmdr. Moonikin Campos — while not a living person — will be in the commander’s seat, and as an unofficial crew member, will play a big role in the mission.

Decked out in a spacesuit and sensors, the "commander" will record the acceleration and vibrations of the launch and mission, plus take radiation measurements as the spacecraft flies through space.

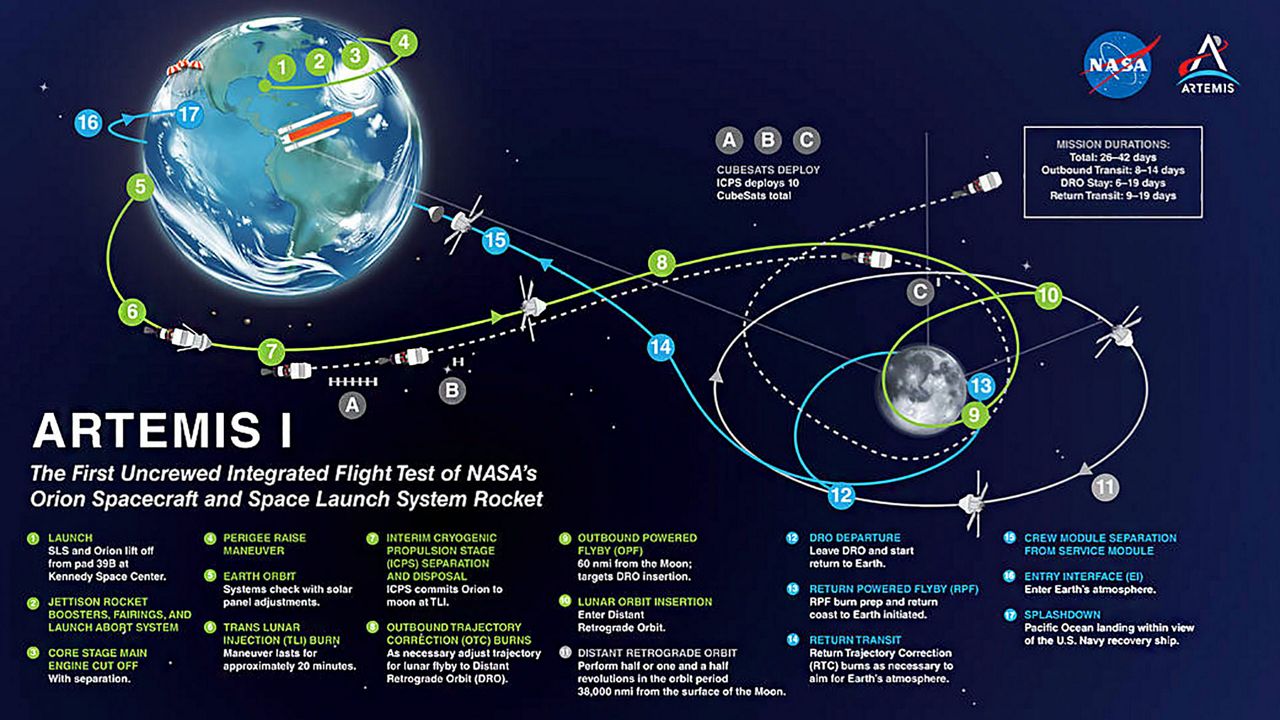

As the brave commander heads to its destination, the engineers on Earth will continue to monitor the Orion craft as it approaches and orbits the moon, stationed about 60 miles above the lunar surface during its closest approach, NASA officials say.

Using the moon’s gravitational force, Orion will be thrust into a distant retrograde orbit, meaning it will go about 40,000 miles past the moon. Experts say that if successful, this is quite an achievement.

“This distance is 30,000 miles farther than the previous record set during Apollo 13, and the farthest in space any spacecraft built for humans has flown,” information from NASA said.

When ready to embark on its return trip, the spacecraft, which can hold up to four astronauts, will use the moon’s gravity to slingshot itself back to Earth before firing its rockets.

When Orion does return home, it will be traveling at speeds up to 25,000 mph before the Earth’s atmosphere slows it down to a mere 300 mph.

And therein lies one of the most important tests of the mission: The speed of returning to Earth. As Orion is speeding along at 300 mph, NASA expects it to produce temperatures of about 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit on the craft itself. This will test the craft’s heat shield's performance, NASA stated.

“Our first and our primary objective is to demonstrate Orion’s heat shield at lunar re-entry conditions. So we want to demonstrate that it can withstand the high speed and high heat that the spacecraft will encounter when it re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere,” said Artemis Mission Manager Mike Sarafin during a teleconference back in July.

The splashdown into the Pacific Ocean off the coast of San Diego is expected to happen on Oct. 10.

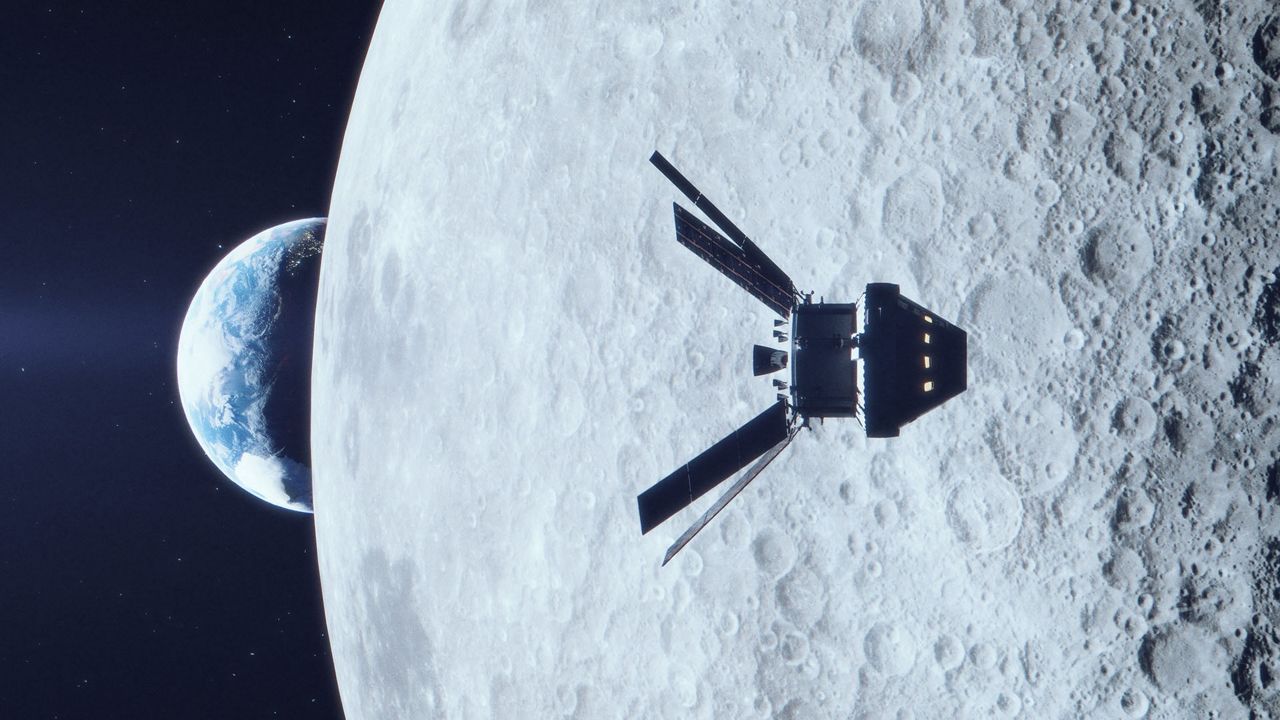

The other Artemis missions and the future

As scientists and engineers unwrap the findings of the Artemis I mission, they will begin to pave a way for future crewed missions.

In 2024, the plan is for Artemis II astronauts to do a flyby of the moon. Using data from that mission, in 2025, Artemis III will send humans back to the surface of the moon.

In fact, during Artemis III, it is expected that the world will see the new Gateway space station in action, which should be orbiting the moon by then.

Being built by both international and commercial partnerships, the Gateway will provide exploration and research support and a place for astronauts to live. But it will not just be for lunar visits — space agencies plan to use it to help with missions to Mars in the coming years.