ORLANDO, Fla. — In return for a lifetime of service to others, including two tours in the Army and years of elementary school teaching, Ulysses Floyd only wanted what was his right in the 1960s: his right to vote.

What You Need To Know

- The Voting Rights Act was passed on August 6, 1965

- The act prohibits policies that stop minorities from voting or registering to vote

- The act was also instrumental in leading to more minority lawmakers

“I thought it was the greatest thing since apple pie. To me, it was a great thing to be able to voice an opinion," said Floyd, now 91. “Some people feel, 'Oh my vote won’t count.' It’s not true. Every vote counts.”

And though he registered when he turned 21, the African-American man conceded that over years, giving his opinion freely was not always easy.

“When they went to the polls to vote, they were questioned about, 'Do you know who you’re voting for,' 'Do you know this?' No one tried to help you," Floyd explained.

“Through a variety of methods, many southern states enacted discriminatory laws. Florida, like most southern states, made it very difficult for black people to vote legally," said Aubrey Jewett, a political science professor at the University of Central Florida.

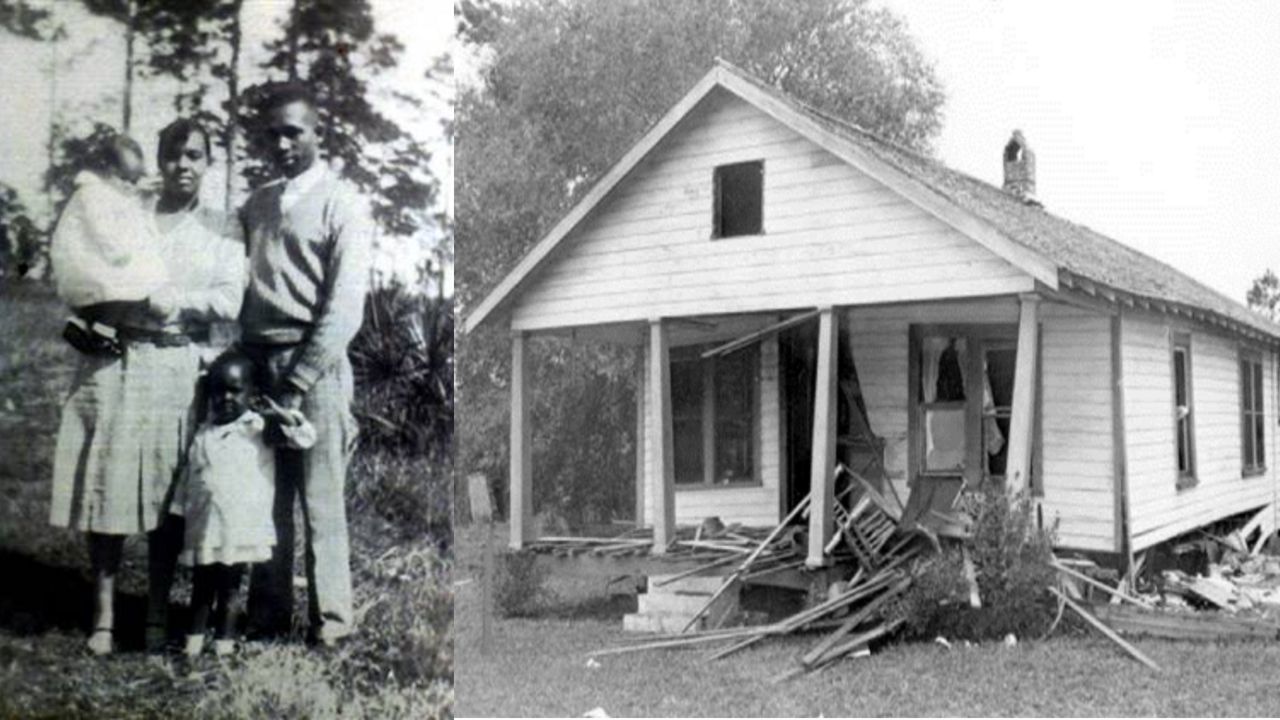

"Then we also had Klu Klux Klan activity, threats of violence. In Brevard County, Harry T. Moore, a civil rights activist and voting activist, and his wife were killed," Jewett added.

Jewett said much changed with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, passed 55 years ago on August 6. The landmark act, signed into law by then-President Lyndon B. Johnson, guaranteed the right to vote to all, regardless of race.

For people of color, it was transformative; its passage gave "federal teeth" to the fight, removing some — but not all — obstacles placed between people of color and the polls, Jewett said.

“The country was saying to us, 'Now we have passed a law'," Floyd said. "I had the right to do it. I didn’t have to worry about trying to fight. As a black person, to be able to do some of the things for my country... I felt good I was able to stand up, not just sit down.”

In the decades following the law's passage, Jewett explained that minority voter registration rates rose, including in Central Florida.

In addition, through redistricting, African-American communities were spliced unfairly less frequently, allowing candidates of color to have a better opportunity to run for elected office.

“You’ve seen a big increase in the number of Black elected officials, in addition to Blacks voting. It’s had wide-ranging ramifications," Jewett said.

In front of his home in Orlando's Lake Mann Estates, a place he has lived in since 1965, Floyd has a number of political signs planted curbside which show his support for Black candidates like Vicki Felder, who is running for the Orange County School Board District 5 seat, and Mikaela Nix, up for Circuit Court Judge.

“If you notice, we have a lot of minorities running for office nowadays. This is important because back in my day, we didn’t have that," Floyd said. “The older people, we kind of set the ground for all that’s going on now. We are the minority, we’ve been suppressed.”

Now, as he watches from the sidelines, new fights for felon voting rights with Amendment Four and for Black Lives Matter, Floyd hopes the progress, built upon generations of struggle, continues.

“I hope it’s a springboard-like effect. That the movement is not going to stop here, but keep elevating until everyone will be equal," Floyd said.