As cities expand, the fast path to growth and urbanization usually means replacing natural land with new roads, more pavement and buildings.

The problem? Unshaded roads and buildings gain more heat during the day and radiate it back to the surrounding area, artificially heating the environment.

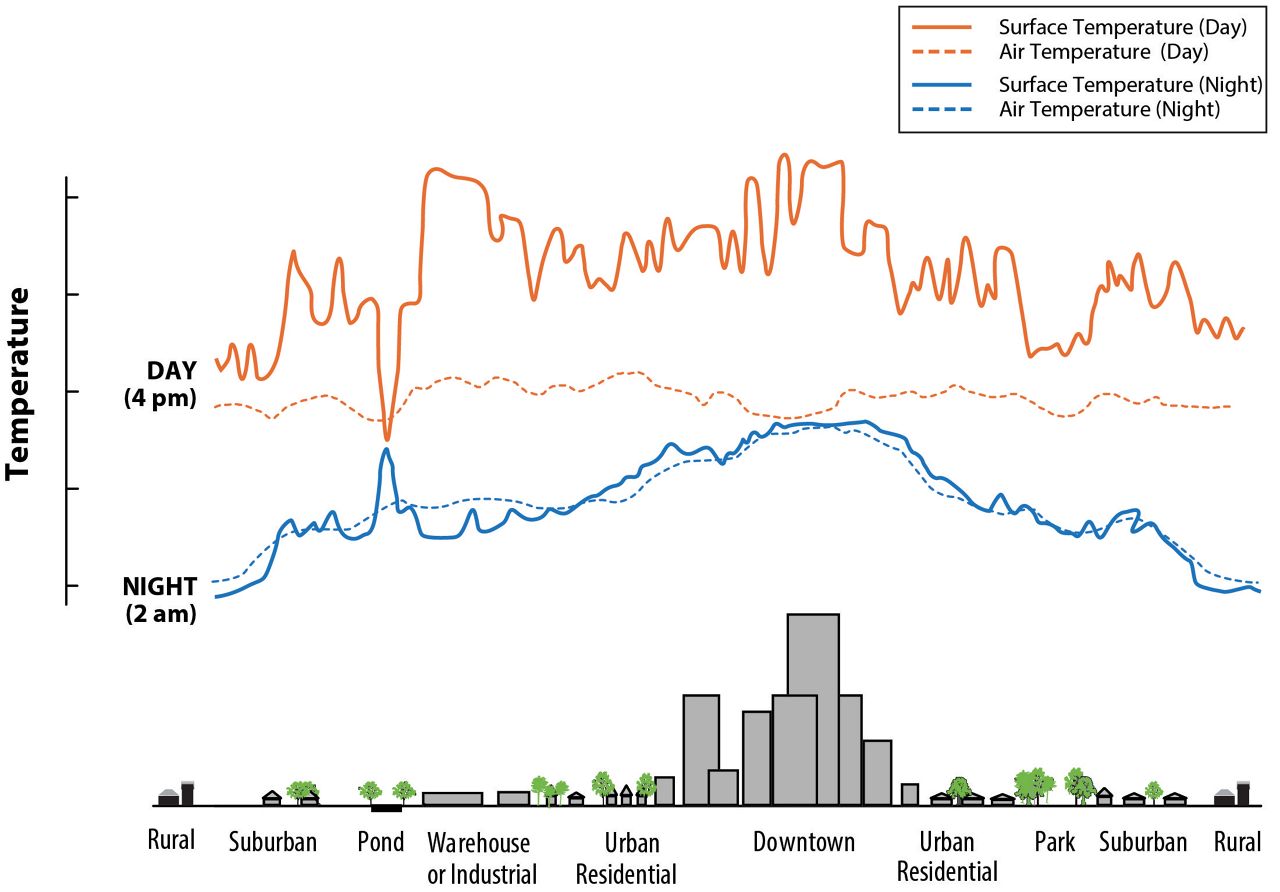

These artificial microclimates become 'urban heat islands,' and can see temperatures increase up to 15 to 20 degrees compared to surrounding vegetated areas in the heat of the afternoon, especially during the summer.

Humans and their development create urban heat islands. Along with urbanization and more roads and buildings, other human activity like cars, air conditioning units and industrial facilities can all emit heat into urban centers.

The temperature difference during mid-afternoon, the hottest part of the day, is more significant than the increase at night because those hot surfaces don’t absorb as much heat overnight.

This diagram from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency shows the characteristics of different heat islands found within a city. It illustrates how parks, ponds and open areas of land can create cooler areas within a city since they don’t absorb the sun’s energy the same way buildings or roads do.

Even suburban and residential areas that include plenty of roads, traffic and buildings don’t have the same type of influence that a crowded downtown area can.

Densely populated urban areas are less likely to have green space, and large buildings can create 'urban canyons,' reducing wind flow.

The best way that cities can combat urban heating is by going green, and there is more than one way to do that.

Planting more trees, increasing vegetation and restoring natural land cover is the most simple way. Trees and vegetation can provide shade to lower temperatures and cool off the surrounding area through evapotranspiration. More trees also improve air quality and help reduce carbon dioxide from the air.

Downtown Orlando is doing exactly that, through an initiative called “Project DTO,” a plan focused on driving positive changes to downtown neighborhoods.

In March 2023, Orlando’s Community Redevelopment Agency planted new Japanese Blueberry trees, Bottlebrush trees and Eagleston Holly trees all throughout downtown. As the trees grow over the next 16 to 18 months, the city can see how they perform in an urban environment.

Project DTO says that they are “working toward a cleaner, greener and cooler sidewalk space for everyone.” Increasing shade coverage and keeping downtown cool, along with improving air quality, is a long-term goal to help improve downtown.

Other strategies include installing green or cool roofs. Adding a vegetative layer or installing reflective surfaces that reflect sunlight away will help reduce roof temperatures, which also helps reduce heating and cooling demands.

Green roofs and urban farming have grown in popularity in large cities to become more environmentally friendly. The Javits Center in New York City is a prime example. In 2021, part of the $1.5 billion expansion plan included a one-acre rooftop farm.

The roof can generate up to 40,000 pounds of produce each year. Along with the leafy greens, zucchini, cucumbers, baby carrots and herbs being grown, a greenhouse on the roof features the only rooftop orchard in the country with 32 apple trees and 6 pear trees.

The roof has the largest rooftop solar array in Manhattan, with 1,400 solar panels providing clean energy to the Javits Center.

The soil on the roof not only keeps it cooler, but it soaks up rainwater, keeping that water out of the sewer system reducing sewage overflow into local waterways.

Our team of meteorologists dive deep into the science of weather and break down timely weather data and information. To view more weather and climate stories, check out our weather blogs section.

Reid Lybarger - Digital Weather Producer

Reid Lybarger is a Digital Weather Producer for Spectrum News. He graduated from Florida State University in 2015 with a Bachelor's of Science in Meteorology. He began his career in local TV news working across Mississippi, Louisiana and Florida for 7 years prior to joining Spectrum in 2022. He's excited for the opportunity to continue to inform the public about the latest weather news with Spectrum.