CINCINNATI — Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel was as unique as his name. The 19th-century Cincinnatian was a West Point graduate who was an attorney, mathematics professor and railroad surveyor. He even served as brigadier general of volunteers for the Union Army during the Civil War.

What You Need To Know

- Known as the “Birthplace of American Astronomy,” the Cincinnati Observatory is one of the oldest astronomy centers in the western hemisphere

- Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel led fundraising to help construct the observatory in the 1840s and then served as its first astronomer

- It moved from its original home in present day Mount Adams to its current site in Mount Lookout in 1873

- While the observation no longer functions well as a research facility, it’s developed a new life as an education center for would-be astronomy lovers

But Mitchel’s lasting legacy is more otherworldly. He led the campaign to build the Cincinnati Observatory, even toiling away by doing some of the construction work himself.

Known as “The Birthplace of American Astronomy,” the Cincinnati Observatory is home to one of the oldest working telescopes in the world. It was also the first public observatory in the western hemisphere.

When Mitchel opened the observatory in 1845, he did so to make astronomy and science accessible for the common person.

An eloquent speaker, Mitchel helped popularize astronomy across the United States. Determined to build an observatory in the Queen City, he raised money by going door-to-door in 1842.

Dean Regas, the observatory’s current astronomer, said Mitchel asked for $25 per person, the equivalent of $876 today.

Mitchel raised more than $9,000 — “an incredible sum of money at the time,” Regas said. It was enough to buy a top-of-the-line telescope in Europe, with a high-quality 11-inch lens.

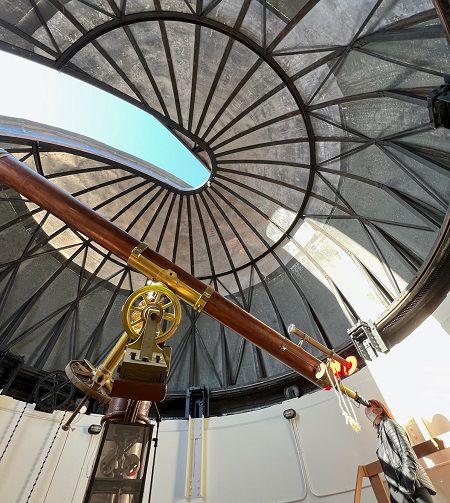

Designers constructed the tube from brass and mahogany and they shipped the completed telescope to New Orleans. The last leg of its journey to Cincinnati was by boat up the Mississippi and Ohio rivers.

They built the observatory around the telescope in a part of town then known as Mount Ida, overlooking downtown Cincinnati. Nowadays, people refer to it as Mount Adams, renamed for President John Quincy Adams after he spoke at the facility’s dedication in 1843.

From its beginning, the Cincinnati Observatory was unlike any other facility of its kind. Back then, its telescope was the third-largest in the world and the University of Cincinnati used it as a key facility for astronomical research and education.

But Mitchel didn’t want to reserve its use for the scientific community alone. He made sure the observatory was also open to the public.

Studying stars and planets wasn’t new in the 1840s, but the belief that information should be available to everyday people was uncommon. Mitchel would sometimes have his research interrupted by visitors who wanted to look through it, Regas said. That helped earn it the nickname of “The People’s Telescope.”

“He was the Carl Sagan or the Neil deGrasse Tyson of his time,” Regas said. “He wanted to bring science and astronomy to everyone and providing access to the telescope was one way to do it.”

To get away from the light pollution of downtown, the telescope moved in 1873 to a new location five miles east of the city. The neighborhood later became Mount Lookout, named in honor of the observatory.

Sitting at the end of a tree-lined street on four acres of hilltop land, the Greek revival-style building is noticeable for its distinctive silver dome. The structure was designed by architect Samuel Hannaford, perhaps best known for two of his later designs — Cincinnati’s Music Hall and City Hall.

In 1904, the observatory purchased a larger telescope from Cambridgeport, Mass. — a 16-inch Alvan Clark and Sons refractor. They built a second building on the campus and moved the older telescope there.

For decades, the Cincinnati Observatory was a top research institution. Mitchel, the first director, wrote and edited the first astronomical publication in the U.S., The Sidereal Messenger.

There’ve been other notable directors over the years as well.

The second director, Cleveland Abbe, published the nation’s first weather forecasts and later helped found the National Weather Service.

Following World War II, Dr. Paul Herget, then the observatory’s director, became a pioneer in using electronic computing machines for astronomical calculations. The Cincinnati Observatory housed the International Astronomical Union Minor Planet Center from 1947 until his retirement in 1978.

Over the years, as technology improved and telescopes became bigger and more powerful, Mount Lookout also became more developed. That caused an increase in light pollution.

As a result, the observatory relinquished its research mission, and the buildings started to deteriorate. In the 1990s, UC — which owns the buildings — even contemplated selling the coveted land to developers interested in building condos, Regas said.

It took a coalition of neighbors, historians, preservation advocates and, of course, astronomers to save the observatory. In 1999, the Cincinnati Observatory was reborn as an education center and a $2.5 million restoration soon followed.

“We’ve got this great population here and (we said), ‘let’s turn that into an attraction and get people really excited about astronomy,’” Regas said. “That transition from research to education was just a huge step and it’s a model that other historic observatories around the country are kind of following.”

Lauren Worley, a member of the observatory’s board since 2018, said transitioning the facility’s mission reflects its founding principle of expanding access to the sciences.

“The concept that you don’t have to be a scientist or academic or even a high-powered patron to have access to the skies reflects that historic commitment to public education and democracy,” she said.

Worley has a unique perspective on the Cincinnati Observatory: She was NASA’s press secretary from 2011 to 2016, before moving closer to home in Ohio.

The realigned mission is a perfect fit for Regas, Worley added. Regas started at the observatory in 2000 as an educator. Although he went to college to become a high school history teacher, Regas stumbled into a side job at the observatory.

“I quickly found out I loved astronomy way more than anything else I’d ever encountered in all my education, so I dove in,” he said. “It’s just one of those things where the stars captured me.”

Regas is always on the search for new ways to share and express his passion for the cosmos.

He’s hosted a podcast, written books, even had a recent residency at the Grand Canyon, which became a frequent topic of his posts on social media. From 2011 to 2019, he co-hosted a long-running syndicated program on PBS called “Star Gazers,” reaching viewers in 100 markets every night for a few minutes to tell them what to look for in the night sky.

“His outreach, and the work of the entire team, would make Mr. Mitchel proud,” Worley said.

Nowadays, various organizations, ranging from school groups to scout troops, tour the facility all the time. The observatory’s telescopes and equipment are also used to support STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) programs in local K-12 schools.

The observatory also hosts community events, including telescope training and “star parties.” People can rent it for weddings, art shows, fundraisers and business meetings.

The Cincinnati Observatory is open to the public every Friday night and some Saturday nights. It also offers daytime programs on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. Since COVID-19, it has reduced some of the telescope availability and uses an appointment system to reserve times.

It hosts an assortment of events throughout the year to coincide with specific astronomical events — planetary alignments, eclipses or lunar events, things of that nature.

Many of the nighttime events at the observatory cater to grownups, such as Late Night Date Nights which offers couples a romantic night under the stars. But there are plenty for the kids, too.

Through its “Future Galileos” project, the Cincinnati Observatory handed out 20 Orion XT8 telescopes to organizations across the region. They also provided safe solar viewing accessories and training so students could observe eclipses.

One of those organizations to receive a telescope is a local nonprofit called Happen, Inc., which provides creative programs to children across the community.

Happen used the telescope to host a “S’more and Stars” event at their headquarters in Northside. They also took program kids to visit the observatory in person.

Echo Lyons, 15, described it as an “amazing experience.”

“The telescope is such a marvel to look both at and through, and the entire tour was fantastic,” Lyons said. “It compelled me to learn about space research and reinvigorated my love for space exploration.”

Lyons’ experience is common among visitors once they peer through the telescope and view the stars above, Regas said.

“It’s just one of those things you don’t forget,” he said. “They came once and they’re hooked. I’ve never heard the word ‘wow’ so much in my life.”