OSCEOLA COUNTY, Fla. — When Kathryn Duart lost hours at work and fell behind on rent at the hotel where she’s been living, she did what she thought she was supposed to do: ask for help.

But hotel management refused to accept federal emergency rental assistance that the mother of two was approved for.

Now, she’s battling an eviction case.

“My rent was always paid a month in advance,” Duart said of her time at Sevilla Inn, the hotel where she and her kids have lived for nearly a year. “I just don’t get why they’re doing this now.”

Her story reflects a question many Floridians have grappled with in the era of pandemic relief: Who may benefit from the nearly $47 billion in emergency rental assistance (ERA) allocated to states and localities by the federal government? Although the Treasury has laid out guidance for local programs charged with administering the funds, in practice, the answer to that question is rarely crystal clear.

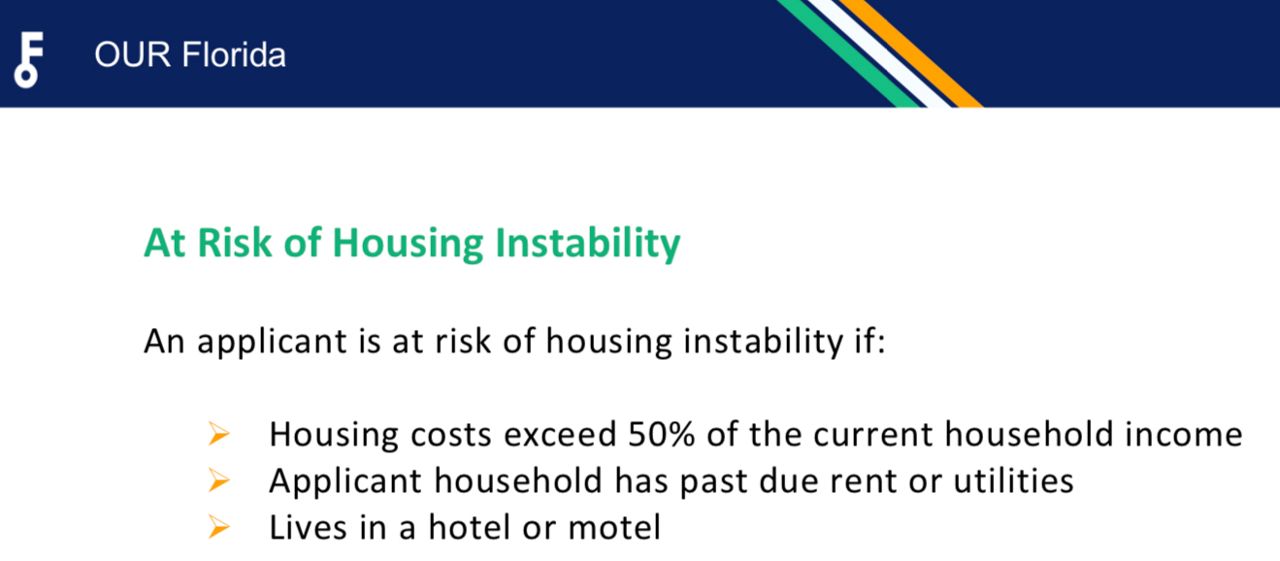

In Duart’s case, she said managers at Sevilla Inn told her ERA funds are only for renters living in more traditional apartments and homes — not hotels. But that’s not true — federal guidelines clearly state the funds can cover “eligible households” for hotel/motel costs. And Our Florida, the statewide program that approved Duart for help, also allows hotel residents to receive assistance, according to a copy of the program’s policy obtained by Spectrum News.

SOURCE: Our Florida

Duart said she asked Our Florida for help after the program approved another Sevilla Inn guest for $7,680 in past and future rent. The hotel accepted that money, per a memo from early November. But they wouldn’t take the $890 check Our Florida sent the hotel on Duart’s behalf, which allegedly ended up in a “return to sender” pile of mail behind the front desk.

Duart said an employee noticed her name written on the check’s note section, and brought it to Duart before it could be mailed back.

Sevilla Inn staff wouldn’t elaborate on whether or not they accept ERA payments on behalf of guests, telling Spectrum News only: “it depends.” Hotel management declined to be interviewed.

“I just think they're giving people the runaround to amuse themselves and hurt people in the long run,” Duart said. “You’re hurting my children, at the end.”

Allowed, but not required: the ERA conundrum

Much of the confusion surrounding ERA stems from layers of state and federal laws governing the programs that don’t always line up, according to attorney Jorge Acosta Palmer of Community Legal Services of Mid-Florida.

“The problem that we’re seeing with emergency rental assistance programs is that they are funded under (and) come from federal law,” Acosta Palmer said. “The way the programs have implemented their programs or procedures do not necessarily align with state law.”

Web Extra Interview

In the case of Florida, where many families living in hotels are considered tenants under state law, confusion may arise from the Treasury’s lack of a specific definition for long-term hotel residents, versus more transient guests.

Generally, if a hotel resident doesn’t have anywhere else to live, they qualify as a tenant under Florida law. Other factors may weigh in, such as whether the resident uses the hotel’s address to receive mail, or on a form of government-issued identification.

But Acosta Palmer said that when it comes to federal ERA guidelines, that nuance shouldn’t really matter. Even if Florida law considers someone to be a hotel guest rather than a tenant, federal ERA guidelines still allow for programs to assist those people, as long as they meet the other criteria.

“Most people that live in motels meet these criteria,” Acosta Palmer said. “They’re below the 80% Area Median Income mark, and the fact that they are living in a motel or a hotel usually helps you prove that you are at risk of homelessness and are facing a financial hardship.”

However, while Treasury clearly provides ERA programs the option to pay for hotel rooms, it leaves it up to those programs to develop policies and procedures for whether – and how – they actually will.

“Even though the ERA programs are allowed to cover hotel and motel expenses, most (local) programs, if not all, have decided not to implement policies and procedures to cover these types of costs,” Acosta Palmer said.

Although Our Florida approved Duart’s application for past due rent, the program wouldn’t cover any prospective rent going forward because she lives in a hotel, according to an email Duart received from program staff in mid-November citing a “policy change.” Yet for people in more traditional residential dwellings, Our Florida will cover up to three months of future rent.

It’s exactly the dilemma Sue Tomb is currently facing at another Osceola County hotel. Management there would gladly accept more ERA payments on her behalf, Tomb said – but because she lives at a hotel, Our Florida won’t approve her to receive them before she falls behind again.

Tomb, a former behavioral specialist for children with autism, is now 61, and struggling to find work she can do with her back and knee pain. While Our Florida previously paid for a past due balance on her room, Tomb was denied this time around because her “residence is not rented or no documented proof of renting a residence,” according to an email.

Tomb said she’s lived in the same hotel for nearly a year and a half, and has provided documentation to prove that. She doesn’t understand why Our Florida won’t help her until she falls behind again, and the hotel formally warns her she’s facing eviction — a process that moves incredibly fast in Florida, beginning only three business days after a tenant receives warning of their past due rent.

“Isn’t Our Florida supposed to keep us from being evicted, keep us from becoming homeless?” Tomb asked.

Going forward, more funding flexibility

For many Florida renters in hotels and more traditional residences alike, by the time ERA funds are approved or paid out, it’s already too late. The eviction process has already started or may even be complete.

Fund disbursement could be expedited considerably, if more programs allowed tenants to receive assistance funds directly. Although for months the Treasury has urged programs to pay tenants directly in cases where landlords won’t participate, that isn’t a firm requirement for ERA1, the federal funds most programs are still working to spend down.

But that’s set to change soon, as programs move through ERA1 and start using their ERA2 allocations from the American Rescue Plan Act. Federal guidelines for ERA2 require programs to pay eligible tenants directly whenever property owners refuse payments themselves.

“Getting to ERA2 is key, because ERA2 is really more flexible than ERA1,” Acosta Palmer said. “Under ERA2, (programs) can just deal with the tenant directly, alone, without ever involving the landlord.”

Per federal guidelines, programs should have already spent or obligated the majority of their ERA1 allocations by Sept. 30 — but many hadn’t, including Our Florida. Those slow-spending programs could soon lose their remaining funds to other, better-performing programs.

Slow programs were required to submit improvement plans to the Treasury by Nov. 15. A spokesperson for the Florida Department of Children and Families, the state agency that hired Our Florida to administer ERA funds, did not say whether or not the statewide program had submitted such a plan.

Acosta Palmer emphasized, low-income tenants who were previously denied ERA funds could be eligible for help going forward.

“These programs have not necessarily done what they’re supposed to, and if they don’t make certain changes, they could be at risk of losing the money,” Acosta Palmer said. “We don’t know what changes they’re going to make, but they might be making changes that mean a tenant that was previously rejected, may be eligible now. So it’s really important for tenants to continue to check what’s happening.”

In the meantime, while Florida eviction law doesn’t provide much leeway for tenants who have failed to pay rent, Acosta Palmer says he’s encouraging clients he works with to raise “good faith defenses.”

“Under landlord-tenant law, everybody – landlord and tenant – they have an obligation of good faith,” Acosta Palmer said. “So the question is, is the landlord acting in good faith when they refuse to participate in ERA, yet they still pursue the eviction?”

Molly Duerig is a Report for America corps member who is covering Affordable Housing for Spectrum News 13. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.