Ever since July, grandmother Jan Bailey-Smith has been trying to make ‘home’ out of a hotel room. The family’s only been staying there a few months, but to six-year-old Ce’Naeyah, it feels like much longer: “A jillion years,” she told Spectrum News 13.

What You Need To Know

- Across all racial/ethnic groups in Orlando, debt-to-income ratio and credit history are the most common reasons home loan applicants are denied (source: Spectrum News 13 exclusive data analysis)

- White Americans are far more likely to inherit family wealth than Black and Hispanic/Latino Americans (source: Brookings)

- 85% of Black college graduates borrow money to cover higher education costs, compared with 69% of white college graduates (source: CRL)

- Understanding the problem: Minorities still encounter obstacles on their path to the American Dream

- Searching for real solutions: Home loan inequality remains, but some people are making progress

- Explaining the methodology behind the data

Together Ce’Naeyah and her older sister, 15-year-old Xhairah, are Bailey-Smith's primary motivation for pushing forward.

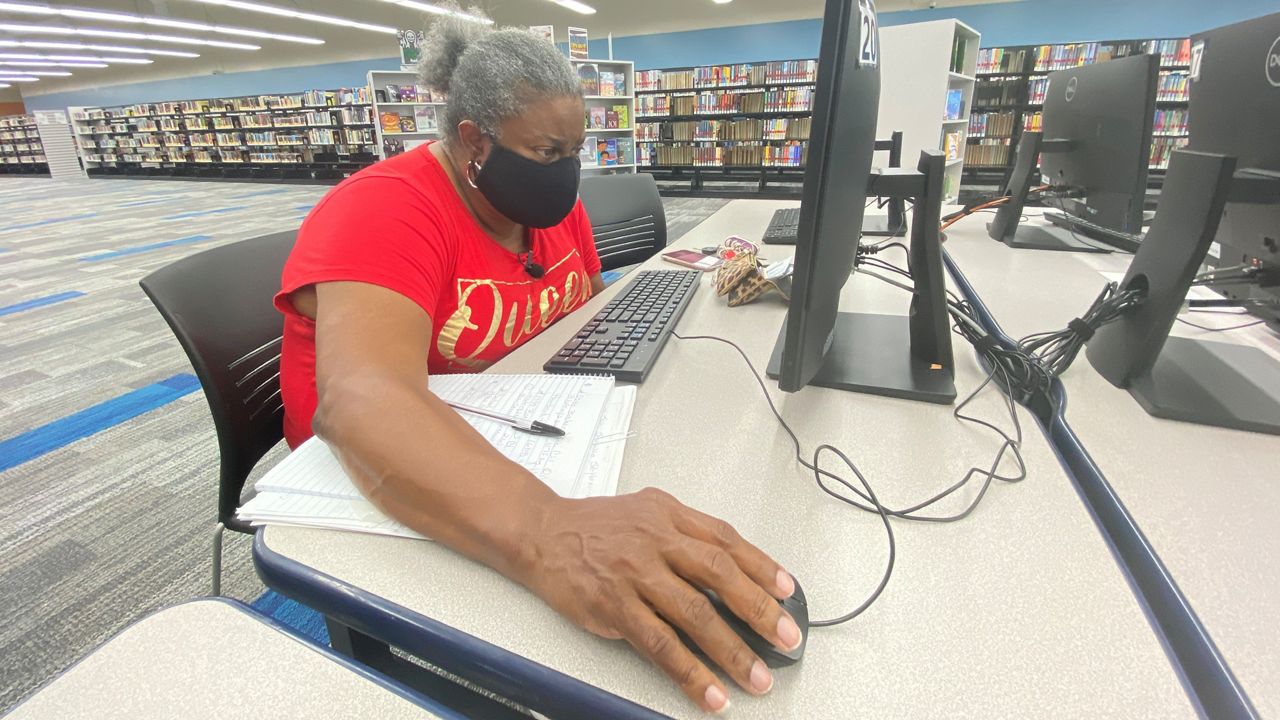

She makes two thirty-minute treks to the school bus stop each morning, leaving before the crack of dawn to drop her older granddaughter off in time. She monitors both girls’ asthma, chasing down pharmacies for the antibiotics and other prescriptions they need. Between chauffeuring the girls to and from school — and making sure they get their homework done — Bailey-Smith spends the rest of her time scouring the internet for affordable housing and assistance.

She also has to squeeze in her own physical therapy and medical appointments, for conditions like diabetes and arthritis. A former traveling claims agent, Bailey-Smith says she kept working to support her family long after doctors advised her to retire — because her own daughter, the girls’ mother, was terminally ill. She died at 32, from diabetes complications, in 2018.

“I just wore myself out, trying to make sure everything would be straight with [my daughter] and the kids,” she said. “That’s just how we’ve always been. It’s just been us, the four of us.”

Now, it’s just the three of them — Jan and her granddaughters — in one small hotel room.

“Ever since my daughter passed … both of them are little worrywarts,” Bailey-Smith said. “They’re always on edge, like something’s gonna happen.”

These days, she says, the girls rarely let her out of their sight. Especially young Ce’Naeyah, nicknamed ‘Ladybug,’ who Bailey-Smith describes as “my daughter all over again.”

Grief may have brought the family closer together emotionally. But Bailey-Smith knows they need more space than they have in their hotel room: somewhere stable and safe, where the girls can spread their wings.

“I promised the girls, this will be our last year renting,” she said.

Her mission, ever since the girls’ mother died, has been to find them a permanent home.

“I’m going to get the credit back in order, and we're going to buy us a nice little house. It’s not going to be a mansion, but we’ll find us a nice little house and then go from there,” Bailey-Smith said.

High prices and a wealth gap

But for Bailey-Smith and so many others, sky-high housing costs are pushing the quintessential ‘American Dream’ of homeownership increasingly out of reach. Nationally, the median price for single-family homes has reached a record high of $310,500. However, in most places, wage increases haven’t kept pace. That means in most of the United States, homeownership is less affordable for average workers than in the last 13 years, according to an analysis from property data firm ATTOM.

It’s even less affordable for Americans without any significant financial reserves to draw from, like a trust fund or family inheritance. Overwhelmingly, these are people of color, as Black and Hispanic/Latino Americans are far less likely to inherit family wealth than their white counterparts. And the inheritances they do receive tend to be far smaller. It’s one big reason why a racial wealth gap persists across all income levels in the U.S., even for families earning in the top 10%. In that highest-income bracket, white families’ average net worth is $1.4 million more than that of Black families.

Growing up, Bailey-Smith describes her family as middle-class. Her mom always worked, and they didn’t lack basic necessities. But they didn’t have tons of extra money to fall back on, either. Once she and her brother were old enough to look after themselves a little more, their mom returned to school, earning her bachelor’s degree.

Bailey-Smith would later earn her own undergraduate degree — and, eventually, an M.B.A. But like 85% of Black college graduates, she had to pay her own way, racking up student loan debt to do it. Now, that debt is one of the biggest roadblocks standing between her and her dream of a ‘forever home’ for the girls.

'There’s gonna be a rainy day'

For years, Vickey Campbell also struggled to find her family’s ‘forever home.’ She ended up having to build it herself.

Since 2018, her Habitat For Humanity home in Apopka has been a welcome gathering place and, ultimately, a beacon of hope for the Campbell family.

“When you do not have anywhere to lay your head, you’re constantly in chaos. You don’t know what’s going on,” Campbell said.

In another moment of her life, Campbell was homeless, just trying to get herself and her six kids through each day. They bounced between the homes of relatives and friends, spending some time living in cars, as Campbell battled chronic health issues all the while.

Now though, she says, she doesn’t have those problems — because as a homeowner, she knows she has a safe space to rely on, not just for herself but for her family. Her mom, Joan, lives here too, and Campbell's oldest son, Danny, often stops by to help with dinner. Together, Danny and Joan help Campbell manage her health conditions, including congestive heart failure and a chronic inflammatory lung disease.

“No matter what’s going on in life … every day I wake up and I’m alive and I got a house, I just thank God,’” she said. “Because a lot of my friends didn’t make it this far.”

While Campbell's undoubtedly grateful for her Habitat home, she does wish a couple parts of the process could have gone differently. For one, she doesn’t understand why her mortgage was sold to a different company shortly after she moved in, or why mildew keeps growing on vents and on the A/C unit of her three-year-old home.

“Read everything, be careful what you’re signing. Be comfortable asking questions,” Campbell said, speaking to other first-time homebuyers like herself.

Looking back, she wishes she would have taken a bit more of her own advice. Habitat requires its future homeowners to complete courses in financial and homeownership education. But Campbell thinks parts of the process moved a bit too quickly.

“You’re rushing to sign papers that are gonna affect you for the rest of your life,” she said. “You’ve got thirty years of my life on the line. Slow down. Let me see what I’m writing and reading.”

Campbell, who never finished high school, says she definitely did learn some things from Habitat’s courses, like tips on budget keeping and how to identify scams. But she also thinks she could have benefited from more discussion on the everyday challenges of homeownership.

“What they don’t really let you know, and I tell people this everyday: there’s always gonna be a rainy day somewhere,” Campbell said. “There’s gonna be a rainy day, and you need to prepare yourself for that.” One of Vickey’s ‘rainy days’ was when she realized she’d have to move to a different bedroom, farther away from the mildew that makes her struggle even harder than usual to breathe.

But still, for Campbell, any rainy days are overpowered by the warm sense of security this home has provided her family. After years of uncertainty and instability, she relishes the fact she finally has a bedroom — with a bed; she shares it with mom Joan, who wakes her up whenever she stops breathing in her sleep.

Most of all, Campbell savors knowing she has something of real value to give her children and grandchildren, an investment for their future and a stronger foundation for their family.

“No matter what you go through, having a place to live is the best thing you can ever own in your life,” she said.

‘You need someone to guide you'

When Beatriz Hernández emigrated from her home country of Colombia in 2006, she, too, was looking for a way to invest in her family’s future. The former psychologist wanted to buy a home she could make all her own: ideally somewhere quiet and close to one of the Orlando universities her three sons would attend. But even though she was financially quite stable and had previously owned homes in Colombia, Hernández's loan application for a home here was rejected — twice.

“When you go to buy a house, you need someone to guide you, even in Colombia,” Hernández said in Spanish. “I don’t know the banking terms, and I can sign something that later turns out to affect me. It’s not only because it’s in English; it’s a very technical kind of language that only experts understand.”

She explained that although the banks she applied with did provide Spanish interpreters, those interpreters weren’t mortgage experts and couldn’t explain terms to Beatriz in a way she fully understood. It wasn’t until she connected with Patty Perez, a local realtor who also happens to hail from Colombia, that Hernández succeeded in getting a loan.

“She carried me through the whole process, took me by the hand, with lots of patience and respect,” Hernández said of Perez. “She’s an economist… she shone light on the financial world for me.”

Perez works with both Spanish and English-speaking clients but says the majority are Hispanic or Latino. They belong to the fastest-growing homebuyer demographic in the U.S., the only group projected to experience a net increase in homeownership rates by the year 2040. In the last ten years, Hispanics/Latinos were responsible for 46% of Florida’s homeownership growth.

Perez says she sees the same trend reflected here in Central Florida, as Hispanic/Latino house hunters make up an increasingly large chunk of the market. Many of them don’t have savings or much financial education, but another huge problem is disinformation. For example, Perez says, some lending institutions won’t tell applicants about assistance programs that could potentially help them, like loans subsidized by state and local governments. So, some applicants walk away thinking they’ll never qualify for a loan, oblivious to the helpful resources that exist.

A big part of Perez's job, then, is to combat the disinformation and distrust many of her clients initially encounter in the American real estate market. To achieve that end, she started a weekly talk show, ‘Casas y casos con Patty Perez,’ which streams on YouTube and 97.9 FM Thursday afternoons. In the show she discusses different aspects of buying a home, including some of the most common mistakes people make when applying for a loan.

“You go through and see, oh my God, I’m committing mistake after mistake,” Hernández laughed, recalling the first few times she watched Perez's show. Before meeting her, Hernández says her biggest mistake was a common one among many Hispanic or Latino homeseekers: she never used a credit card, so she hadn’t established a credit history.

“I don’t like to owe money to a bunch of people,” Hernández explained. “I saw girlfriends of mine, who had like eight credit cards all maxed out, and I was like, no, I don’t like that. It seemed stressful to me.”

In the Orlando area, credit history is one of the most common reasons Hispanic/Latino applicants are denied for home loans. Some, like Hernández, prefer paying cash to racking up plastic debt. Others distrust banks, instead choosing to keep “cash hidden in their homes,” Perez says.

But Perez taught Hernández the importance of spending — responsibly — with a credit card. After building up her credit score, Hernández finally got her loan in 2019, giving her the chance to build the family foundation she’d always dreamt of.

Now, Hernández is thrilled to be able to garden with her husband in the backyard, throw birthday parties and host other gatherings with loved ones. She even found a home right in the part of town she wanted, a quiet East Orlando neighborhood close to UCF.

It took awhile for Hernández to achieve her goal of homeownership, and it wasn’t the most straightforward path. But despite those initial denials, she is adamant there was no racial or ethnic discrimination at play.

“It’s not that they rejected me. It was that I didn’t meet their requirements,” she said.

'We just want something safe and clean'

Back at the hotel, Jan Bailey-Smith catches up with her granddaughters after the school day. She reads a note from Ce’Naeyah’s teacher about her nonstop talking this morning — “What was that about, Ladybug?!” — and tries to keep the girls on track with homework, answering their questions as they arise.

But some questions she can’t answer. Like why the family was evicted from their rental apartment in July, even after Orange County approved Bailey-Smith for federal emergency rental assistance (ERA) that could have kept her and the girls stably housed while she recovered from the pandemic’s economic fallout.

Despite months of U.S. Treasury guidance urging state and local governments to loosen requirements and speed up their distribution of ERA funds, Orange County’s program still requires landlord participation. Just like many other ERA programs across the country, Orange County won’t release approved funds until landlords agree to accept the money and present basic tax documentation.

Bailey-Smith's former property owner refused, so the family was evicted: a glaring stain on her rental history that will likely discourage most future landlords from renting to her. Eviction disproportionately affects Black women more than any other group, keeping families like Bailey-Smith's locked into cycles of poverty.

One day, Bailey-Smith says she wants to start a nonprofit to help struggling single women find affordable housing for their families. One day, she hopes she can motivate others by sharing her own success story. First, she just has to bring that story to life.

“We’re not looking for the White House. We just want something safe and clean, in a community where the kids have their classmates and their friends,” Jan said. “That’s all we want.”

Molly Duerig is a Report for America corps member who is covering affordable housing for Spectrum News 13. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.