ORLANDO, Fla. — Just a few weeks ago, Sam Johnson didn’t have a home to call his own. But that all changed after he stopped by SALT Outreach, a mobile outreach center that helps people experiencing homelessness in downtown Orlando.

What You Need To Know

- A Central Florida mobile outreach center serving homeless people plans to expand its reach to Sanford

- SALT Outreach is fundraising to build permanent affordable housing units out of shipping containers

- Leaders of the group say they've noticed more clients seeking help who are new to homelessness

- RELATED:

“I want to say it was by accident, but nothing is really by accident,” Johnson says of the way he stumbled upon the nonprofit, a faith-based organization that provides daily showers, laundry services and donated goods to people in need. From their central location on the Christian Service Center’s downtown campus, SALT (Service And Love Together) staff can also help quickly connect homeless people with resources from other assistance organizations.

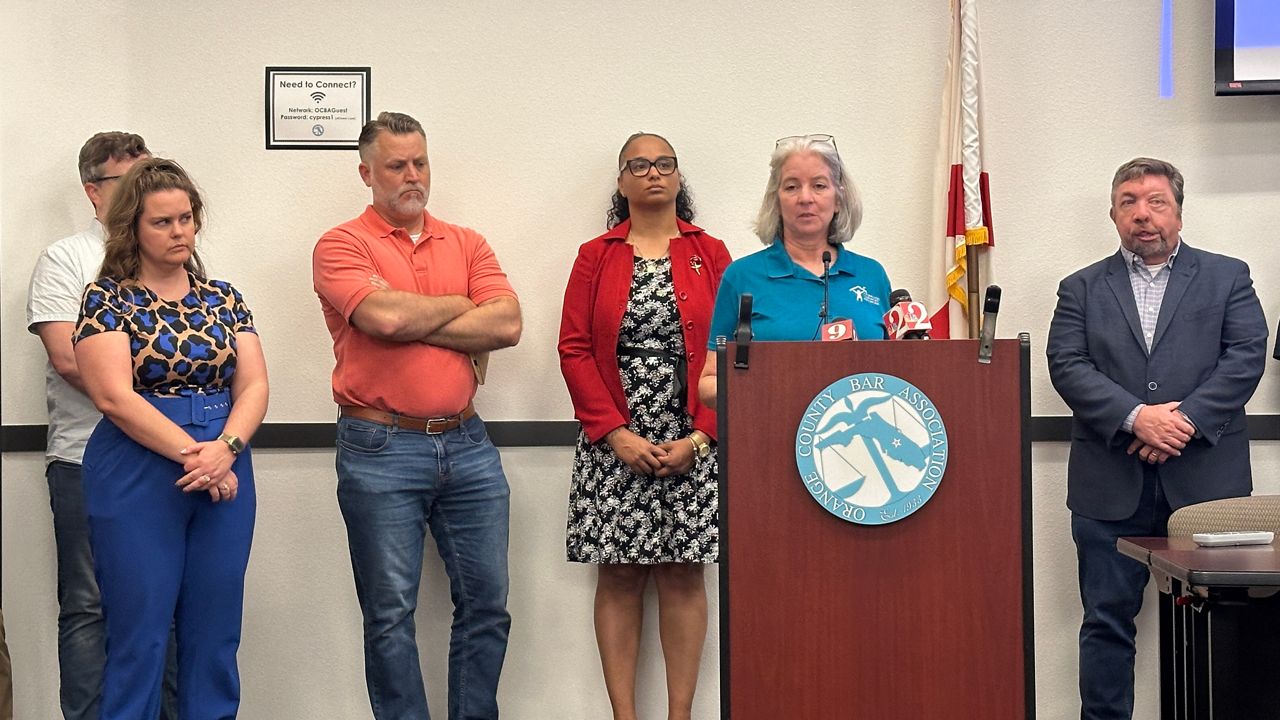

SALT Outreach President Eric Camarillo, who founded the organization in 2011, says the group helps fill gaps between what local homeless people need and services other local aid groups are able to provide.

“Being flexible, finding out what those needs are and meeting them in a creative way has really been a bedrock to what we do here,” Camarillo said.

Although SALT itself isn’t a housing provider, when Johnson came seeking help, Camarillo and his caseworkers were able to connect him to an affordable living situation.

Now, Johnson says he and his new roommate are “inseparable” in their stable rental home.

“We believe that social integration plays a key role in not only getting someone housed and empowering someone to be housed, but also keeping them housed,” Camarillo said.

New to homelessness

Johnson’s just one example of someone who’s new to homelessness – a trend Camarillo says appears to be growing amid job losses, evictions and other financial turmoil wrought by the pandemic.

“Last year, we were seeing basically on average two new people to homelessness every time we operated,” Camarillo said. “Now, it’s been three to four new people, every time we operate.”

Between January 2019 and January 2020, federal data shows the total number of people experiencing homelessness in the U.S. rose by 12,000. That jump was driven entirely by an increase in the unsheltered population: people sleeping outside, as opposed to in shelters. It’s still unclear what impact COVID-19 will ultimately have on the size of the country’s homeless population, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

“The sad thing about it is the lack of affordable housing in this area. There just isn’t enough,” Camarillo said. “Over and over, (we) hear housing’s the biggest thing... and there just isn’t housing to give. It just weighs on you.”

Not one to sit idly by when there’s a problem at hand, Camarillo says he began thinking creatively about how SALT could help address Central Florida’s affordable housing deficit in a cost-effective way.

That’s how the idea for tiny home trailers came about.

Now, up in Sanford, contractors are working to retrofit 40-foot shipping containers into duplexes, which Camarillo says will eventually become permanent, supportive housing for people experiencing homelessness. SALT’s initial goal is to raise $200,000 over the next year to bring eight units to life.

“The goal is to really help make it feel like a home for someone,” Camarillo said. “We’ll charge a low percentage of their income for them to actually live here.”

It’s SALT’s way of trying to help fill Florida’s affordable housing deficit. No state in the country has enough rental housing for its poorest residents, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition — but Florida is in a particularly dire position as the fifth-ranked most challenging state for extremely low-income people to find housing.

Camarillo hopes that as SALT continues to grow, it can serve even more of the people who suffer most from Florida’s affordable housing gap. Along with the trailers, the group will also soon offer shower/laundry services in Sanford – once a week to start, although Camarillo dreams of expanding to operate there five days a week, like in Orlando.

SALT is also building a street outreach team of social workers to proactively seek out more people who are homeless — or, as SALT staff say, “homebound” — and engage them for services.

“We prefer to call them ‘homebound,’ because they’re bound to get a home,” said Natalia Alvarez, a case manager for SALT. “Your words have a big impact on empowering others.”

‘Get back on the highway’

When Johnson found SALT, he was reeling from financial strife, intensified by his grief about losing his wife of over 30 years. After she fell sick and passed away in 2019, Johnson says he left their Fort Lauderdale home for Orlando, seeking a fresh start and a distraction from the painful memories.

“No matter where I went, I saw her,” Johnson says of his late wife.

In Orlando, Johnson worked day gigs, eventually scoring a permanent janitorial position. Then, the pandemic hit.

“That just brought a screeching halt to everything,” Johnson said.

In the months that followed, Johnson was trapped in a state of housing insecurity, jumping between local shelters and hotels, where he says he’d spend about 65% of his income on housing. That’s more than double the 30% share widely accepted as the limit for how much someone can affordably spend on housing costs.

But now, thanks to SALT and its community partners, Johnson is stably housed, paying $600 a month for the room he shares with a new friend. At the most recent hotel, he says he paid nearly half that amount — almost $300 — for just three days.

“As human beings, we learn to adapt to any given situation,” Johnson said. “Everybody that's out there that's homeless doesn’t particularly want to be. But they find themselves adapting to their surroundings.”

His advice to anyone struggling with homelessness is to not be so quick to adapt, and to maintain focus on a path forward.

“If you get off at the wrong exit, for every exit, there’s also an entryway back on the highway,” Johnson said. “Get back on the highway.”

Molly Duerig is a Report for America corps member who is covering affordable housing for Spectrum News 13. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.