OSCEOLA COUNTY, Fla. — To an unsuspecting passerby, it might initially look like the Kukec family is doing OK.

But the swimming pool at the Kissimmee house where they’re staying isn’t theirs. One of 9-year-old Livia Kukec’s favorite toys is a dollhouse she crafted from a cardboard box. And after July, the family doesn’t know where they’ll be sleeping next.

What You Need To Know

- An Osceola family has been experiencing housing insecurity for more than a year

- The Kukec family even has access to federal assistance

- Osceola County’s housing-choice voucher program differs from federal policy

- The vast majority of domestic violence victims also suffer financial abuse

“I’ve said a lot, and my kids have said it: we’ll just say, we want to go home,” Amy Kukec says, tears welling up in her eyes. “We don't know where home is, but we just want to go home.”

It’s been this way for the past 18 months, ever since Kukec arrived in Central Florida with her two young children after fleeing an abusive relationship in Illinois that she says almost killed her. She is now on disability, the result of a back injury from that relationship.

With an eviction and a past bankruptcy on her record — both results of the financial abuse Kukec says she endured — it’s been nearly impossible for her to find stable housing. Ninety-nine percent of domestic violence survivors report having also experienced financial abuse, according to one study.

Victims often end up in the position Kukec finds herself now: saddled with a low credit score, a past eviction and bankruptcy on her record.

“People usually leave with nothing,” Kukec said. “Not just without your material things. You leave with literally, financially, your ability to do nothing to help yourself.”

Since late 2019, Kukec’s daughter says she guesses they’ve moved in and out of at least 15 different hotels, motels and short-term rentals in Central Florida.

Mom Amy Kukec says her daughter's incredibly creative- but seeing this is also incredibly heartbreaking

— Molly Duerig (@mollyduerig) July 15, 2021

“A lot of people, when they hear the word ‘homeless,’ they think of people that live on the street or in a tent. That’s not exactly true. It’s not a 1-size-fits-all,” she said pic.twitter.com/LTHeZ7V1b6

How vouchers do — and don’t — work

Kukec says she first got on a waitlist for a federal housing choice voucher — also known as a Section 8 voucher — in 2016, back in Illinois. When she arrived in Osceola County in late 2019, she got on the waitlist in Florida. In June, she was finally approved, but so far, she says the voucher hasn’t helped her.

“The most challenging part of being given a voucher after waiting so many years is that you can’t use it anywhere,” Kukec says. “Especially with the inflation of rent right now.”

Housing-choice vouchers are designed to help very-low income, elderly and disabled people find safe, stable housing, by providing a subsidy to offset the cost of rent. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) distributes vouchers to public housing agencies across the country, which then administer programs locally.

Once someone is approved for a housing-choice voucher, he or she has a set amount of time to find a safe, sanitary rental property with an owner who is willing to accept vouchers as payment. But based on Osceola County guidelines, the cost of that rental property can’t exceed a certain monthly amount — what HUD calls the “payment standard.” The payment standard is used to calculate how much assistance a recipient can receive, based on fair-market rent — essentially, the amount of money that’s generally needed to rent a moderately priced unit in the local housing market.

With rent prices skyrocketing in Central Florida and across the country, Kukec says she can’t find any three-bedroom units in Osceola County for $1,644: the maximum monthly rent she’s allowed to search for based on a document signed by county staff in late May and provided by Kukec to Spectrum News.

After researching the federal program herself, Kukec initially believed she’d be able to rent a slightly pricier unit with her voucher, if she could front the cost of the difference herself. According to HUD guidelines, “a family which receives a housing voucher can select a unit with a rent that is below or above the payment standard.”

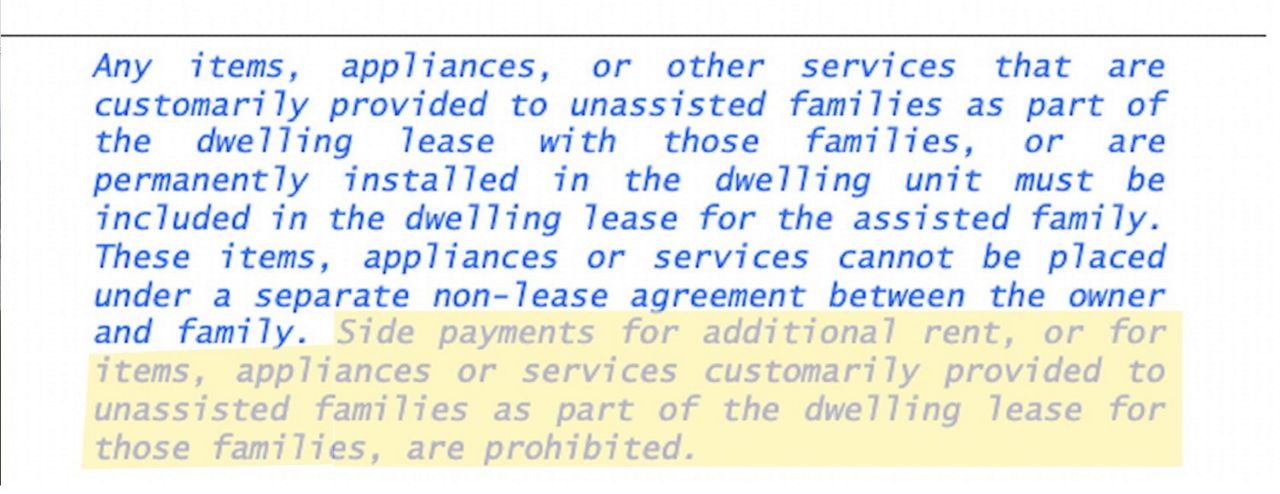

But local housing agencies can set their own guidelines. Osceola County’s policy doesn’t allow voucher recipients to pay any more than the designated payment standard, according to staff and the county’s administrative plan, which prohibits “side payments” between tenants and landlords.

Danicka Ransom, assistant director of human services for Osceola County, says that’s because the county’s main focus is on “long-term affordability” for voucher recipients.

If a recipient signs a lease agreement for a higher amount, “that means every month, they’ve got to come up with $200 extra from somewhere that we don’t know about because it’s not part of their household income,” Ransom says.

“If they ever can’t get that money, you can face eviction. And if you're evicted, you lose your voucher permanently,” Ransom says.

But right now, with prices as high as they are, Kukec wonders if she — and her children — will ever get into a home to begin with. After more than a year of shuffling around, mostly during the COVID-19 pandemic, they say they are feeling beyond discouraged about their odds of finding stability.

“There’s no child in the world that deserves to live like this at all,” Kukec says. “And there’s no parent who deserves to not have the opportunity to provide their children with a place to live because the system won’t let them.”

A ‘golden ticket’?

Research indicates it’s fairly common for housing-choice voucher recipients to lose their vouchers involuntarily, before getting a chance to use them. Multiple studies have indicated that “many families give the voucher up involuntarily because of misunderstandings or issues with the administration of the voucher program,” according to a 2009 report from Harvard University.

There’s a difference between relinquishing a voucher while it’s actively in use, versus never actually getting a chance to use it in the first place. The former scenario “just doesn’t happen” in Osceola County, Ransom says.

“Because of the simple fact it's so hard to get on the program as it is, when you get it, it's almost like the golden ticket,” Ransom says.

But she acknowledges that sometimes people do lose access to vouchers, if they run out of search time while trying to find a rental they can afford where the landlord accepts vouchers.

“Most of the time when that occurs, the family is just being very selective on where they want to live,” Ransom says.

If recipients absolutely can’t find housing despite their best efforts, Ransom says county caseworkers may intervene to help, by extending search-time limits and/or negotiating with landlords for slightly lower rent payments. Kukec recently received a two-month extension from the county, giving her until late September to find housing.

In a late-June email exchange provided by Kukec to Spectrum News, Kukec expressed her frustration to county staff, saying the voucher was offering help she couldn’t even use. She pleaded with the county to let her pay the difference between her payment standard and the rent prices she was seeing.

“From what I have researched, I can pay over the amount, is that correct?” Kukec wrote. “My son wants to go to school with his friends. He's starting [sic] jr high and has been through enough trauma.”

A county staff member replied to Kukec, including in the message an excerpt of the county’s administrative program plan. “I advise that you negotiate your rent with the potential landlord,” the staffer wrote at the end of their email.

For Kukec, her main concern is stability for her children. Her 11-year-old son wants nothing more than to stay in the same school district with his friends, she says.

Despite all their challenges, Kukec is still trying to look forward and think positively about ways to fix a system she characterizes as “completely broken.” She has ideas for national legislation she’s nicknamed “New Beginnings” — a bill that would help domestic violence survivors who have endured financial abuse.

“It’s something you could never imagine. I could have never imagined it myself, before I was in this situation,” Kukec says. “I would have thought myself that there was help for people like me, and there just isn’t.”

Molly Duerig is a Report for America corps member who is covering Affordable Housing for Spectrum News 13. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.