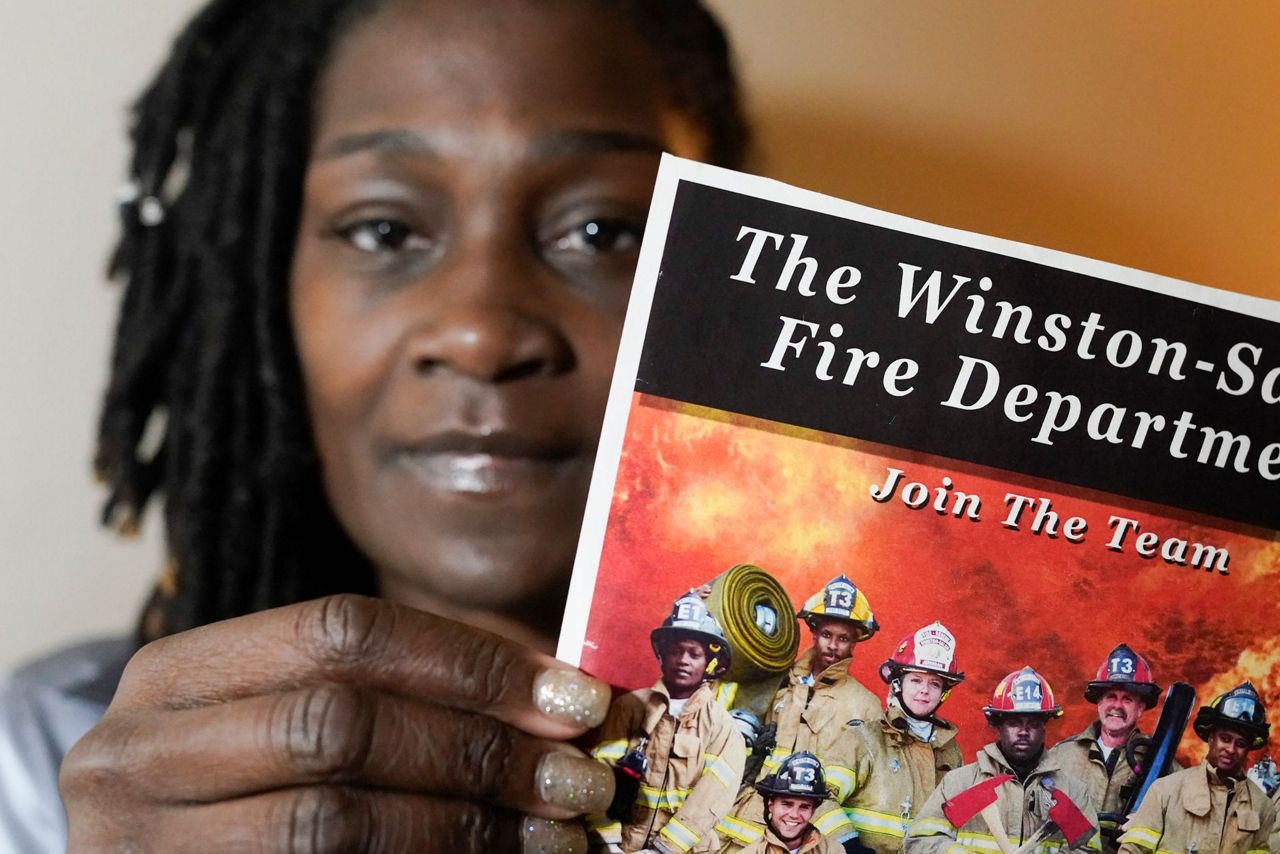

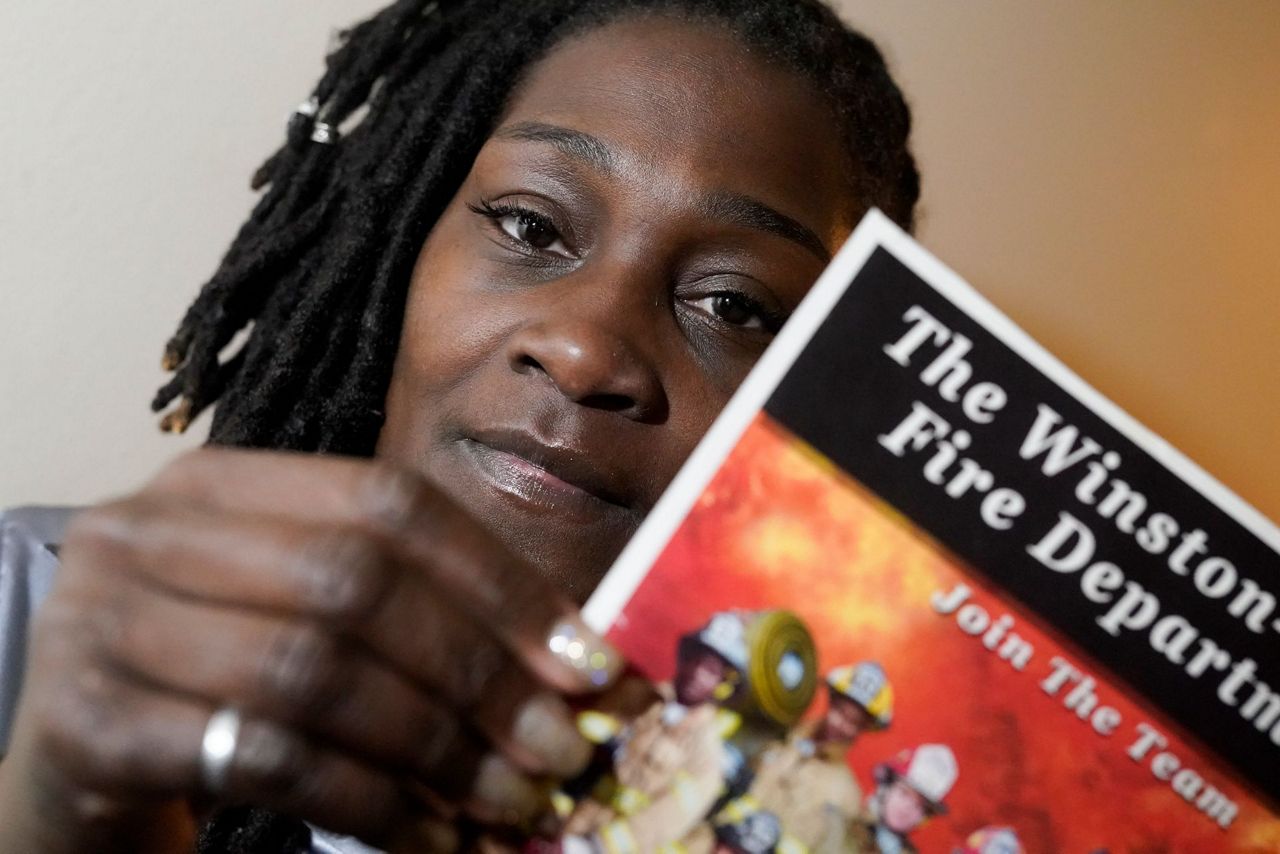

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. (AP) — They threw her new cellphone on the roof of the station house and placed nails under the wheels of her pickup truck. As she prepared to answer a call, someone poured tobacco juice in her boots. It was too much for Timika Ingram to bear.

“It caused me pain, sleepless nights, suffering, anxiety,” said Ingram, whose four years as a firefighter in North Carolina amounted to a collection of indignities.

Other Black firefighters who endured similar treatment in the Winston-Salem Fire Department recently brought their complaints before the city. The grievance they filed in October calls for Chief William “Trey” Mayo to be fired for failing to discipline white firefighters who, the group said, have created a hostile work environment through comments in person and on social media.

“It's a festering problem that has become even more disease-ridden and even more detrimental to the life of the individuals who work here because of the current chief,” said 28-year veteran firefighter Thomas Penn, a leader of the group that calls itself Omnibus.

Across the country, firefighters are confronting incidents of racism and discrimination as part of a burgeoning movement to call out and address racial injustice in America.

Two Black women sued the city of Denver in September, saying its fire department discriminated against them because of their gender and race. One alleged a captain overseeing her training said she should “keep her head down and act like a slave” to graduate from the program.

Last year, a Black firefighter sued city officials in Lansing, Michigan, saying they did nothing to stop racial discrimination within the fire department after he received hostile comments and found a banana on his assigned firetruck’s windshield. He filed another lawsuit this summer.

A white Delaware firefighter was charged in July with hate crimes and harassment after allegedly sending threatening messages to a Black paramedic and two part-time workers, one who is Black and the other white who has Black family members, the News Journal reported.

The Winston-Salem group alleged two white captains talked about running over demonstrators protesting the police killing of George Floyd, and that a firefighter made a noose during a rope and knots class in November 2017.

City Manager Lee Garrity cited the state's personnel privacy law in declining to comment. He said the city has launched a so-called “climate assessment” through a Charlotte-based firm, which will evaluate the entire fire department regarding diversity, race, gender and sexual orientation. A report is due by year's end, he said.

“We'd had very few grievances or complaints in the last couple of years,” Garrity said. “But I am sure there are opportunities for improvement.”

Mayo didn't return multiple phone calls seeking comment.

In early November, Penn said the climate assessment hadn't begun and added in an email that department administrators, including Mayo, “has attempted to intimidate and bully our members" by walking in during interviews.

Ingram said of her treatment throughout rookie school, “You develop alligator skin so that you can get on through the process. And then, hopefully, once you get in, you'll be able to be an advocate or be able to be heard if anything goes on, because a lot went on with me.”

She officially joined the department in July 2006. Almost right away, she said, other firefighters stole her food and took her uniforms out of her personal space.

The cellphone incident was a significant factor in Ingram's eventual departure because, without it, her three children had no way to reach her. She said her white counterparts asked if she'd actually left her phone where it was last seen and even pretended to search for it.

“My daughter was a latchkey kid at the age of 9. My kids had no other way to get in touch. They didn't know how. Something went wrong with my kids, and I couldn't get to them and they couldn't get to me,” she said. “That right there just set it off.”

Ingram was transferred and expressed concerns over her treatment to a superior who didn't address them, she said.

“I was like, 'I’m fighting a losing battle.' You can talk all you want, say what you got to say,” she said.

In July 2010, Ingram quit. Her life spiraled downward for a time. She said she married someone “to mask the pain,” but that ended in divorce. Her car was repossessed and she was homeless. She missed work for four months, and doctors told her she developed lupus as a result of the stress she'd undergone as a firefighter.

Retired Winston-Salem firefighter Gary Waddell experienced discrimination on a different plane in 1989 because of his marriage to a white woman who visited him at the station shortly after he was assigned there.

“I didn't think anything of it, but when my wife came inside of this fire station, I was told by my supervisor, who was a captain, that my wife could no longer come to the station to visit me,” Waddell said. “But the other members of my crew that I was working with, their wives could come by. But mine couldn't. So that's how I started my career.”

Today, Ingram works in medical services in Charlotte, the same job she took after leaving the fire department. She worked out a deal to get her car back, and she's pursuing a degree in psychology. But she still thinks about the career she had to abandon.

“I just wished I could have stayed,” she said. “I really do, because I worked hard to get there. I trained to get there.”

Copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.