NEW YORK (AP) — Deep in the bedrock 15 stories below the famous Grand Central Terminal, a cavernous construction site is slowly, and expensively, taking shape as a commuter rail hub that will accommodate more than 150,000 passengers a day.

East Side Access has been dogged by massive cost overruns and delays since construction began nearly a dozen years ago. But Gov. Andrew Cuomo has brought in a manager who is focused on bringing the $11 billion project to completion by a new deadline in four years.

"We can all see the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel," said Janno Lieber, who came to the state-run Metropolitan Transit Authority a year ago, drawing upon his private-sector experience planning the rebuilding of skyscrapers around the World Trade Center.

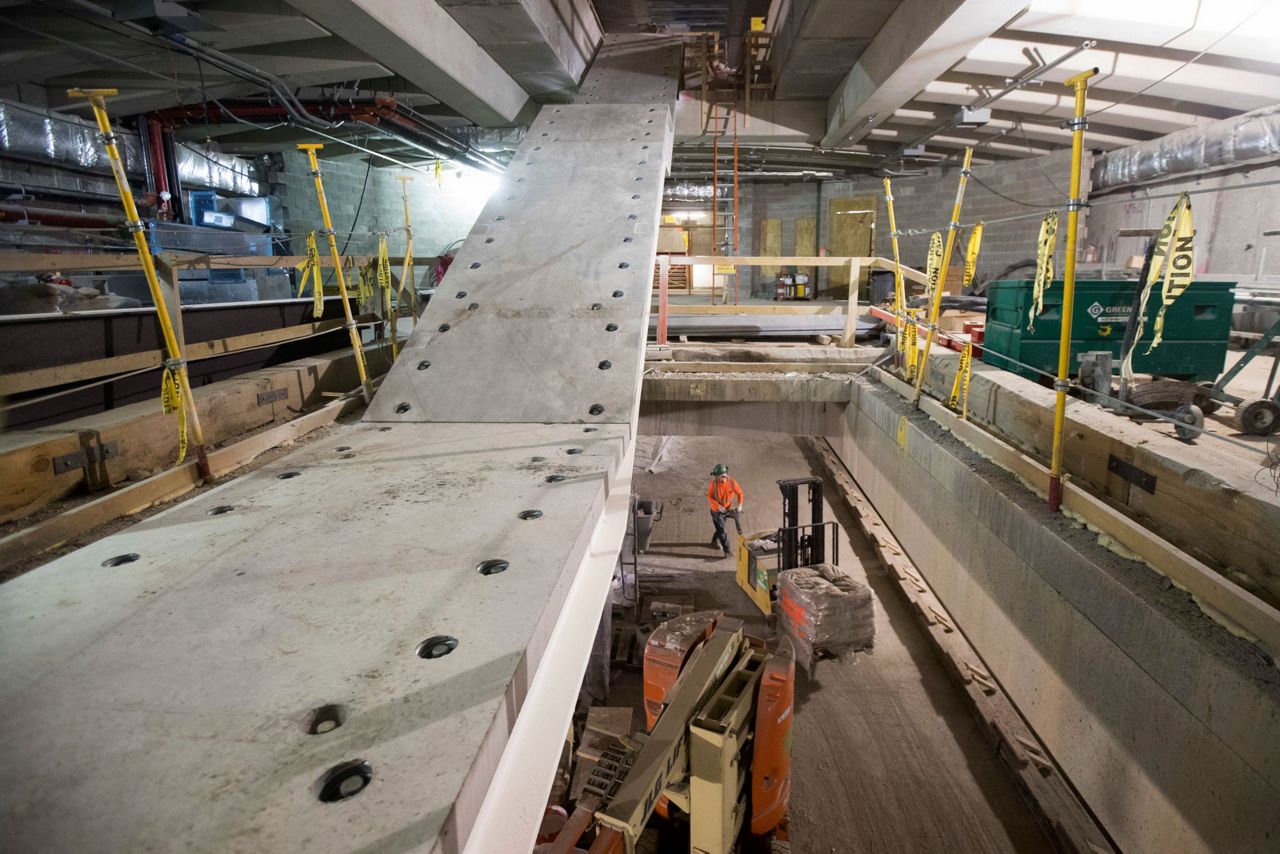

Massive boring machines that excavated the space have been replaced by workers clanging, sawing and hammering against concrete and steel to create a concourse and two levels of platforms with eight tracks in all.

The aim is to create a new, direct route for riders of the Long Island Rail Road to and from Manhattan's East Side, alleviating traffic that currently flows through the chaotically congested Penn Station, on the island's West Side.

On a recent morning, MTA officials led a walking and stair-climbing tour to showcase progress on the unfinished, cavern-like terminal with ceilings as high as six stories. Dozens of high-speed escalators are being built to lead down to a 350,000-square-foot (32,516-square-meter) LIRR concourse with marble already laid on its walls and space reserved for retail shops and dining areas.

It will be the hub for 8 miles (13 kilometers) of new tunnels blasted and drilled out from 400 million-year-old bedrock, winding their way under Park Avenue and the East River and on to Queens and Long Island.

It is all focused on alleviating some of the pain for about 150,000 LIRR commuters who must somehow get to and from Grand Central every day. Currently, they have to joust, push and elbow their way to platforms at crowded Penn Station, which also accommodates Amtrak and New Jersey Transit trains, adding up to 40 minutes to their daily commutes.

For years, critics have pounced on unforeseen construction they say has been mired in politics, bureaucracy and disorganization.

MTA officials have blamed such factors as the difficulty of carving through the bedrock, the need to work around an active transportation system, and the challenge of carting away 75,000 truckloads of rock, mud and other refuse. Much of it was used as fill in parks and other projects.

But there are other reasons for work moving at a snail's pace, says Kathryn Wylde, chief executive officer and president of the Partnership for New York City, a business community group.

The MTA has 75,000 employees, including managers, she said, and the result is a massive bureaucracy with multiple agencies that all want to be involved in decisions, no matter how small. In an effort to speed things up, the governor has become the de facto "project manager" of East Side Access, Wylde said.

Cuomo brought in Lieber and other private-sector and government professionals who are allowing contractors more flexibility in dealing with details or unexpected circumstances, Wylde said.

"The challenge is, can they move the bureaucracy to get things done?" she asked.

Lieber says he is focused on hitting the Dec. 31, 2022, deadline.

"We now, at the MTA, are determined," he said. "We're changing the culture of construction management and development at the MTA."

___

This story has been corrected to show that the number of tracks is eight, not 16.

Copyright 2018 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.