IZIUM, Ukraine (AP) — The first time the Russian soldiers caught him, they tossed him bound and blindfolded into a trench covered with wooden boards for days on end.

Then they beat him, over and over: Legs, arms, a hammer to the knees, all accompanied by furious diatribes against Ukraine. Before they let him go, they took away his passport and Ukrainian military ID — all he had to prove his existence — and made sure he knew exactly how worthless his life was.

“No one needs you,” the commander taunted. “We can shoot you any time, bury you a half-meter underground and that’s it.”

The brutal encounter at the end of March was just the start. Andriy Kotsar would be captured and tortured twice more by Russian forces in Izium, and the pain would be even worse.

Russian torture in Izium was arbitrary, widespread and absolutely routine for both civilians and soldiers throughout the city, an Associated Press investigation has found. While torture was also evident in Bucha, that devastated Kyiv suburb was only occupied for a month. Izium served as a hub for Russian soldiers for nearly seven months, during which they established torture sites everywhere.

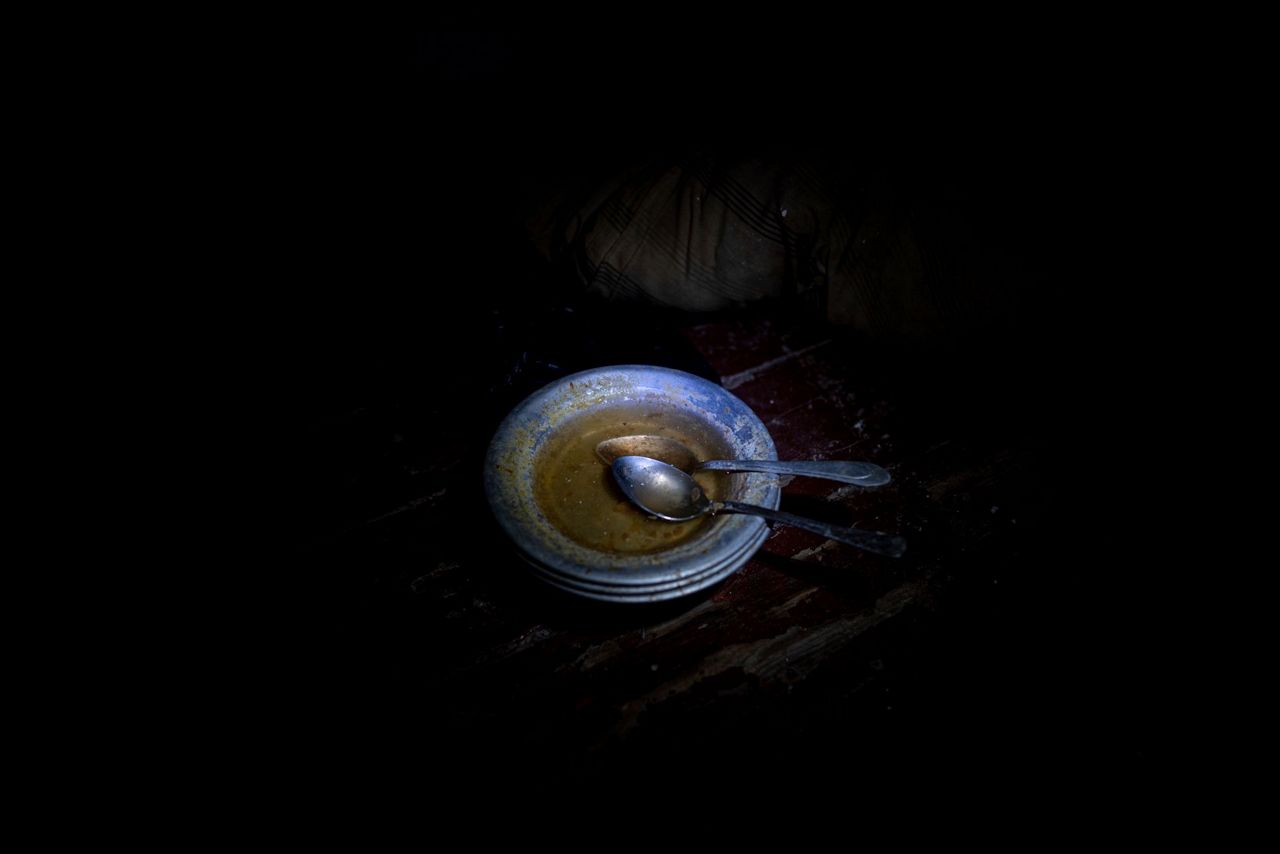

Based on accounts of survivors and police, AP journalists located 10 torture sites in the town and gained access to five of them. They included a deep sunless pit in a residential compound with dates carved in the brick wall, a clammy underground jail that reeked of urine and rotting food, a medical clinic, a police station and a kindergarten.

The AP spoke to 15 survivors of Russian torture in the Kharkiv region, as well as two families whose loved ones disappeared into Russian hands. Two of the men were taken repeatedly and abused. One battered, unconscious Ukrainian soldier was displayed to his wife to force her to provide information she simply didn't have.

The AP also confirmed eight men were killed under torture in Russian custody, according to survivors and families. All but one were civilians.

At a mass grave site created by the Russians and discovered in the woods of Izium, at least 30 of the 447 bodies recently excavated bore visible marks of torture — bound hands, close gunshot wounds, knife wounds and broken limbs, according to the Kharkiv regional prosecutor’s office. Those injuries corresponded to the descriptions of the pain inflicted upon the survivors.

AP journalists also saw bodies with bound wrists at the mass grave. Amid the trees were hundreds of simple wooden crosses, most marked only with numbers. One said it contained the bodies of 17 Ukrainian soldiers. At least two more mass graves have been found in the town, all heavily mined, authorities said.

A physician who treated hundreds of Izium’s injured during the Russian occupation said people regularly arrived at his emergency room with injuries consistent with torture, including gunshots to their hands and feet, broken bones and severe bruising, and burns. None would explain their wounds, he said.

“Even if people came to the hospital, silence was the norm,” chief Dr. Yuriy Kuznetsov said. He added that one soldier came in for treatment for hand injuries, clearly from being cuffed, but the man refused to say what happened.

Men with links to Ukrainian forces were singled out repeatedly for torture, but any adult man risked getting caught up. Matilda Bogner, the head of the U.N. human rights mission in Ukraine, told the AP they had documented “widespread practices of torture or ill-treatment of civilian detainees” by Russian forces and affiliates. Torture of soldiers was also systemic, she said.

Torture in any form during an armed conflict is a war crime under the Geneva Conventions, whether of prisoners of war or civilians.

“It serves three purposes,” said Rachel Denber of Human Rights Watch. “Torture came with questions to coerce information, but it is also to punish and to sow fear. It is to send a chilling message to everyone else.”

NO SAFE HAVEN

AP journalists found Kotsar, 26, hiding in a monastery in Izium, his blond hair tied back neatly in the Orthodox fashion and his beard curling beneath his chin. He had no way to safely contact his loved ones, who thought he was dead.

Back in March, after his first round of torture, Kotsar fled to the gold-domed Pishchanskyi church. Russian soldiers were everywhere, and nowhere in Izium was safe.

Hiding amid the icons, Kotsar listened to the rumble of Russian armored vehicles outside and contemplated suicide. He had been a soldier for just under a month and had no idea if anyone in his little unit had survived the Russian onslaught.

When he emerged from the church a few days later, a Russian patrol caught him. They kept him a week. His captors’ idea of a joke was to shave his legs with a knife, and then debate aloud whether to slice off the limb entirely.

“They took, I don’t know what exactly, some iron, maybe glass rods, and burned the skin little by little,” he said.

He knew nothing that could help them. So they set him free again, and again he sought refuge with the monks. He had nowhere else to go.

By then, the church and monastery compound had become a shelter for around 100 people, including 40 children. Kotsar took up a version of the monastic life, living with the black-robed brothers, helping them care for the refugees and spending his free hours standing before the gilt icons in contemplation.

In the meantime, Izium was transforming into a Russian logistical hub. The town was swarming with troops, and its electricity, gas, water and phone networks were severed. Izium was effectively cut off from the rest of Ukraine.

SCREAMS IN THE NIGHT

It was also in the spring that the Russians first sought out Mykola Mosyakyn, driving down the rutted dirt roads until they reached the Ukrainian soldier’s fenced cottage. Mosyakyn, 38, had enlisted after the war began, though not in the same unit as Kotsar.

They tossed him into a pit with standing water, handcuffed him and hung him by the restraints until his skin went numb. They waited in vain for him to talk, and tried again.

“They beat me with sticks. They hit me with their hands, they kicked me, they put out cigarettes on me, they pressed matches on me,” he recounted. “They said, ‘Dance,’ but I did not dance. So they shot my feet."

After three days they dropped him near the hospital with the command: “Tell them you had an accident.”

At least two other men from Mosyakyn’s neighborhood, a father and son who are both civilians, were taken at the same time. The father speaks about his two weeks in the basement cell in a whisper, staring at the ground. His adult son refuses to speak about it at all.

That family, along with another man who was also tortured in the basement cell on Izium’s east bank, spoke on condition of anonymity. They are terrified the Russians will return.

Mosyakyn was captured again by a different Russian unit just a few days later. This time, he found himself in School No. 2, subject to routine beatings along with other Ukrainians. AP journalists found a discarded Ukrainian soldier’s jacket in the same blue cell he described in detail. The school also served as a base and field hospital for Russian soldiers, and at least two Ukrainian civilians held there died.

But the soldiers again freed Mosyakyn. To this day, he doesn’t know why.

Nor does he understand why they’d release him just to recapture him a few days later and haul him to a crowded garage of a medical clinic near the railroad tracks. More than a dozen other Ukrainians were jailed with him, soldiers and civilians. Two garages were for men, one for women and a bigger one — the only one with a window — for Russian soldiers.

Women were held in the garage closest to the soldiers’ quarters. Their screams came at night, according to Mosyakyn and Kotsar, who were both held at the clinic at different times. Ukrainian intelligence officials said the women were raped regularly.

For the men, Room 6 was for electrocution. Room 9 was for waterboarding, Mosyakyn said. He described how they covered his face with a cloth bag and poured water from a kettle onto him to mimic the sensation of drowning. They also hooked up his toes to electricity and shocked him with electrodes on his ears.

It was here that Mosyakyn watched Russian soldiers drag out the lifeless bodies of two civilians they’d tortured to death, both from Izium’s Gonkharovka neighborhood.

Kotsar was taken to the clinic in July and received a slightly different treatment, involving a Soviet-era gas mask and electrodes on his legs. AP journalists also found gas masks at two schools.

By the time Kotsar arrived, people had already been there for 12 to 16 days. They told him arms and legs were broken, and people had been taken out to be shot. He vowed that if he survived, he would never allow himself to be captured again.

They released him after a couple of weeks. He craved familiar faces and people who meant him no harm. He returned to the monks.

“When I came out, everything was green. It was very, very strange, because there had been absolutely no color,” he said. “Everything was wonderful, so vivid.”

SHALLOW GRAVE

In mid-August, the bodies of three men were found in a shallow forested pit on the town’s outskirts.

Ivan Shabelnyk left home with a friend on March 23 to collect pine cones so the family could light the samovar and have tea. They never came back.

Another man taken with them reluctantly told Shabelnyk’s family about the torture they’d all endured together, first in the basement of a nearby house and then in School No. 2. Then he left town.

Their bodies were found in mid-August, in the last days of the occupation, by a man scavenging for firewood. He followed the smell of death to a shallow grave in the forest.

Shabelnyk’s hands were shot, his ribs broken, his face unrecognizable. They identified him by the jacket he wore, from the local grain factory where he worked. His grieving mother showed the AP a photo.

“He kept this photo with him, of us together when he was a small boy,” said Ludmila Shabelnyk, in tears. “Why did they destroy people like him? I don’t understand. Why has this happened to our country?”

His sister, Olha Zaparozhchenko, walked with journalists through the cemetery and looked at his grave.

“They tortured civilians at will, like bullies,” she said. “I have only one word: genocide.”

The Kharkiv region’s chief prosecutor, Oleksandr Filchakov, told the AP it was too soon to determine how many people were tortured in Izium, but said it easily numbered into the dozens.

“Every day, many people call us with information, people who were in the occupied territories,” he said. “Every day, relatives come to us and say their friends, their family, were tortured by Russian soldiers.”

MISSING NO MORE

After his final escape, Kotsar hid in the monastery for more than a month. Without documents and a phone connection to prove his identity, he was too afraid to leave.

Kotsar’s family had no idea what happened to him. They had simply reported him missing, like so many other Ukrainian soldiers caught on the wrong side of the frontline.

He spoke with effort to AP journalists, and at one point asked them to turn off the camera so he could compose himself. The AP contacted the Commissioner for Issues of Missing Persons Under Special Circumstances, which confirmed the missing person report and his identity through a photo on file. Then Kotsar’s own unit, which had left Izium in disarray, returned and tracked him down.

Kotsar doesn't know what comes next. Ukrainian officials are still in the process of restoring his identity documents, and without them he can’t go anywhere. He would like psychological treatment to deal with the trauma from repeated torture, and for now he’s staying with the monks.

“If it weren’t for them, I probably wouldn’t have survived at all,” he said. “They saved me.”

Kotsar’s first call was to the sister of his best friend — the only person in his entire circle of loved ones he was certain was in a safe place. He grinned as the connection went through.

“Tell him I’m alive,” he said. “Tell him I’m alive and in one piece.”

___

Sarah El Deeb contributed from Beirut.

___

Follow the AP’s coverage of the war at https://apnews.com/hub/russia-ukraine

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.