NEW DELHI (AP) — Dr. L.N. Dhar vividly remembers the cold morning in Kashmir nearly 30 years ago. He left behind his plush bungalow and a prestigious job at a government hospital, becoming a refugee on the run almost overnight, with nothing but a small bag hurriedly stuffed with whatever clothes and cash he could grab.

He was heeding warnings blared over loudspeakers outside mosques in the Muslim-majority region and on graffiti on walls and windows across the main city of Srinagar.

Kashmiri Hindus got three options: convert to Islam, leave or be killed, Dhar said.

"For a peace-loving citizen, for an educated class of people, our option was that we left that place," he said near his home in New Delhi. "That was the only option. We had no other choice."

Now, Dhar and thousands of other Kashmiris Hindus native to the South Asian region could get an opportunity to return to their homeland after India's Hindu nationalist-led government suddenly stripped political autonomy from its part of Kashmir, tightening its grip in the restive region. But many are wary.

Kashmir's special status dates to 1947, when India and Pakistan won independence from British rule. Each claimed the region, and they have fought two of their three wars over it, with each now controlling part of it.

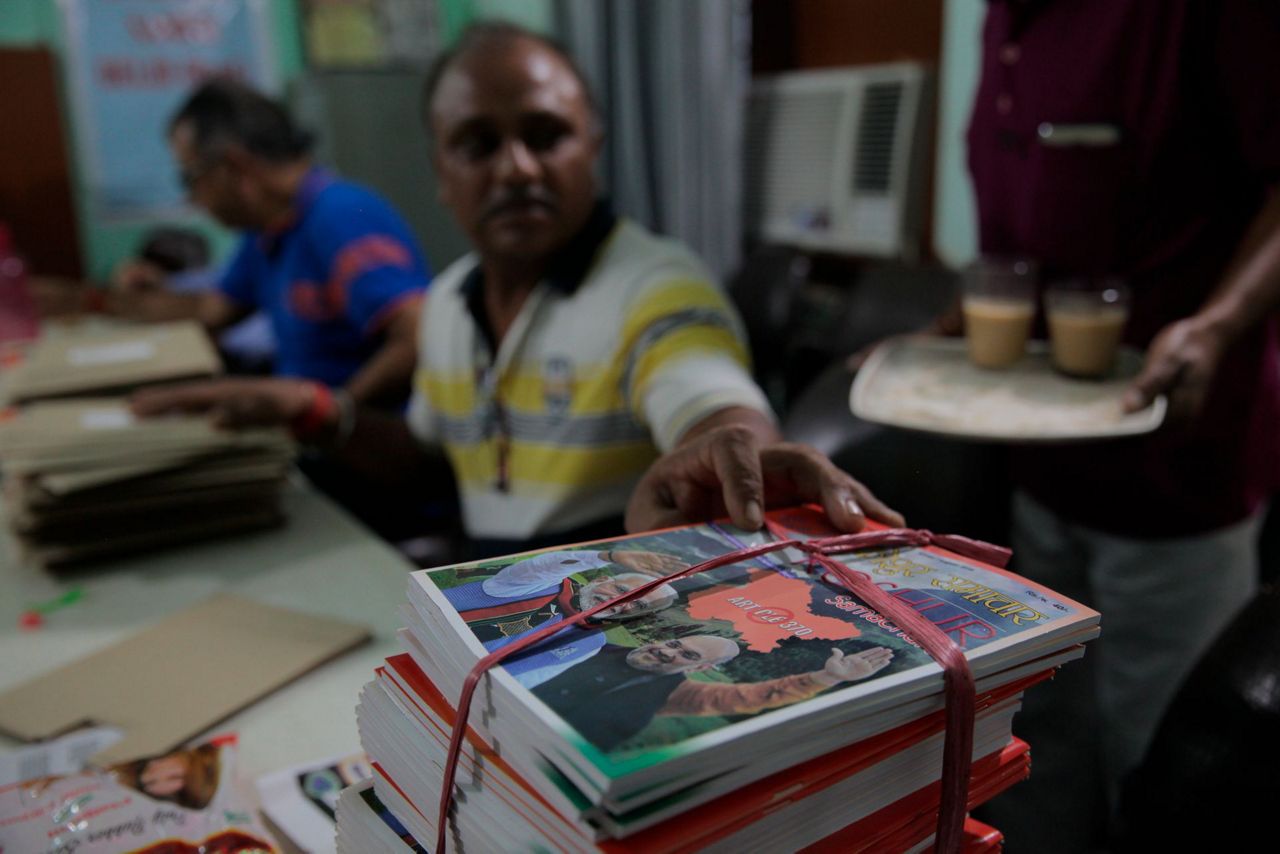

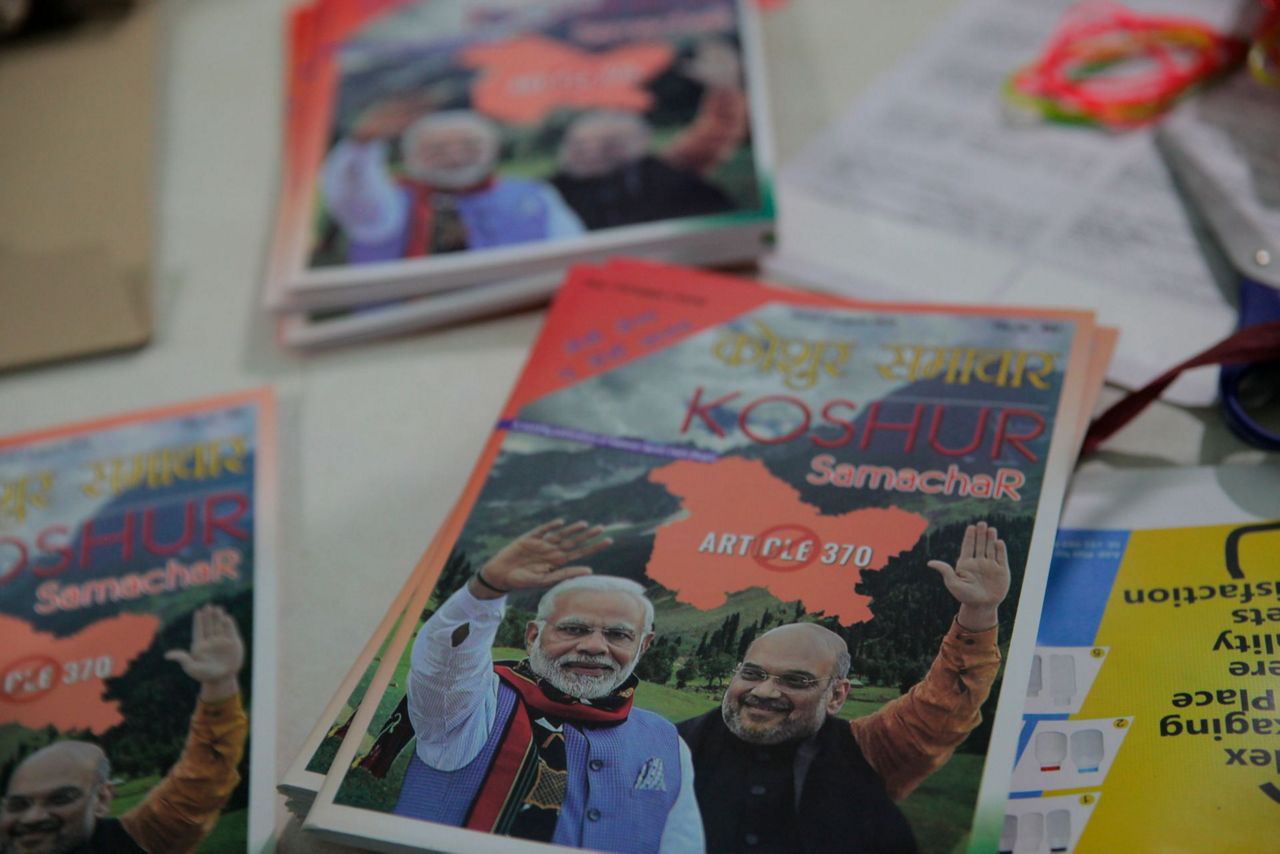

The decision to end the status was widely celebrated by Kashmiri Hindus across India — in sharp contrast to the barricaded streets of Srinagar and sporadic but short-lived protests against the government's move.

India imposed a security and communications lockdown before the Aug. 5 decision to avoid an uprising in its only Muslim-majority state, Jammu and Kashmir. Mobile phone services have yet to be restored, leaving Kashmir almost isolated from the rest of the world. A curfew is in place, and Kashmiri leaders have been detained.

In 1990, Dhar and his family were among more than 60,000 families that fled the alpine forested Himalayan valley, leaving behind homes, land and other property that many would never retrieve.

It was the beginning of one of the bloodiest decades in Kashmir's tormented history, with violence that killed tens of thousands, including Hindu and Muslim civilians, armed rebels and Indian security forces.

Separatist political groups calling for an independent Kashmir had built weapons caches and were gaining popular support. In response to attacks by armed rebels, the Indian government in September 1990 extended a law that gave its armed forces authority to arrest or kill in Kashmir with no or little warning to try to maintain order.

What ensued was near-unabated violence that has turned Kashmir into a battleground.

Vijay Kaul, 72, reminisces about life in the picturesque valley, before the violence began.

"One of the best things about the people of Kashmir was that there was a sense of unity among them, no matter what religion they belonged to," said Kaul, a Kashmiri Hindu whose family had lived in a 170-year-old palatial home near Srinagar for centuries.

While an insurgency against Indian rule strengthened in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with attacks on government forces and ultimately Kashmiri Hindus, Kaul stayed put with his family.

At first, he didn't heed warnings from separatists because of his belief in "Kashmiriyat" — which means an eternal state of peace, harmony and living to help each other.

It wasn't until an explosive went off near a compound wall of his residence that they decided to leave. He and his wife, Varuna, packed whatever they could and set off with their two young children for the city of Jammu — the state's Hindu-majority pocket.

"That was the most terrifying night of my life," Varuna Kaul said. "It was only after we crossed over to Jammu that I felt relieved."

Anywhere from 150,000 to 300,000 Kashmiri Hindus have fled since 1990, according to the Indian government. But Kashmiri Hindu organizations say that is a drastic underestimate.

Panun Kashmir, a New Delhi-based organization that demands a separate state for Kashmiri Hindus, estimates the number of displaced Hindus at 700,000.

Kashmiri Hindu families moved to migrant camps that were later converted into housing complexes in Jammu and New Delhi. Many have pending court cases accusing people in Kashmir of encroaching or seizing their properties there.

But even if they win those cases, many Kashmiri Hindus believe it is not safe to return.

Many view revoking Kashmir's special status as a step in the right direction for justice, but they demand more be done.

Sumeer Chrungoo, president of Kashmiri Samiti, an organization of Kashmiri Hindus in New Delhi, said they "will not return to the same environment they had left."

"If we go back, we will go with conditions that uphold our honor and dignity," he said.

Others, like Vijay Kaul, urge the government to show restraint and resolve the issue peacefully.

"There needs to be a strong stress on brotherhood and living in peace. Everyone has the right to live, to speak and to dissent. There is no religion higher than humanity," Kaul said.

___

Associated Press journalist Channi Anand contributed to this report from Jammu.

Copyright 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.